Executive Summary

The Final Budget Outcome provides surprisingly frank numbers on the O’Neill government’s inexcusably poor management of government revenues, expenditures and debt.

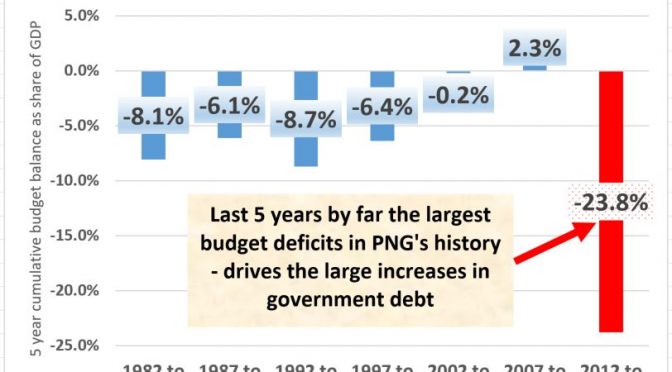

This document confirms a budget deficit and debt blow-out during 2016. PNG has never before -even during much worse falls in commodity prices – had such an appalling string of huge budget deficits.

The government has no credible path out of the budget mess. Deficit levels are getting larger, not smaller.

PNG Treasury states the debt to GDP ratio is 32.6% and so exceeds the 30% limit set out in the Fiscal Responsibility Act (and using the GDP series when this benchmark was created, it is now 42.7% of GDP).

As a result of the failure to manage this fiscal crisis, PNG’s debt in 2016 is 258% of its 2012 levels. This will be a painful legacy for PNG’s future as little of the debt blow-out has been properly invested.

The 2016 Supplementary Budget assumed that revenues would increase by K928 million but the FBO indicates revenue actually fell by K1,236.7 million – a difference of K2,164.7 million.

The Supplementary Budget also assumed that expenditures would be cut by K928 million but they were only cut by K262.2m. Staffing costs actually exceeded the Supplementary Budget by an extraordinary K471.0 million (mainly due to poor planning around teachers). There is a risk that some of the K1,102.7 million reduction in goods and services expenditure late in 2016 is simply a deferral of bills.

The blow-out in deficits and debt results from excessive expenditure expansion in 2013 combined with a dramatic collapse in revenues to the lowest levels since Independence. The revenue collapse mainly results from the poor performance of the PNG economy and the diversion of revenues to Kumul Petroleum – less than 30% of the revenue fall is due to the fall in commodity prices.

The poor budget outcome in 2016 also means revenues will be lower and expenditures higher than shown in the 2017 budget. The 2017 budget needs to be redone.

Details

The PNG Treasury released the 2016 Final Budget Outcome report on 31 March 2017. It is available on its website through the following link. Overall, the report is a credit to the professionalism of the staff of PNG’s Treasury.

This PNG Treasury report confirms what the Treasurer said on the same day when “spilling the beans” on economic mismanagement in PNG – see a link to his presentation here.

Possibly for political reasons, the Treasurer has agreed to release some rather damning numbers that I did not think would come out before the election. The frankness of the FBO reveals a split between the Treasurer’s National Alliance and the Prime Ministers’ Peoples National Congress. Even then, I expected the PM’s minders to catch these embarrassing numbers.

Using GDP numbers based on older PNG Treasury projections or IMF projections, the deficit and debt blow-outs are even worse.

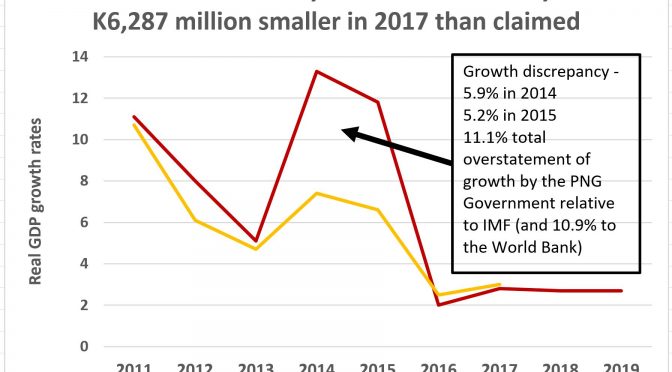

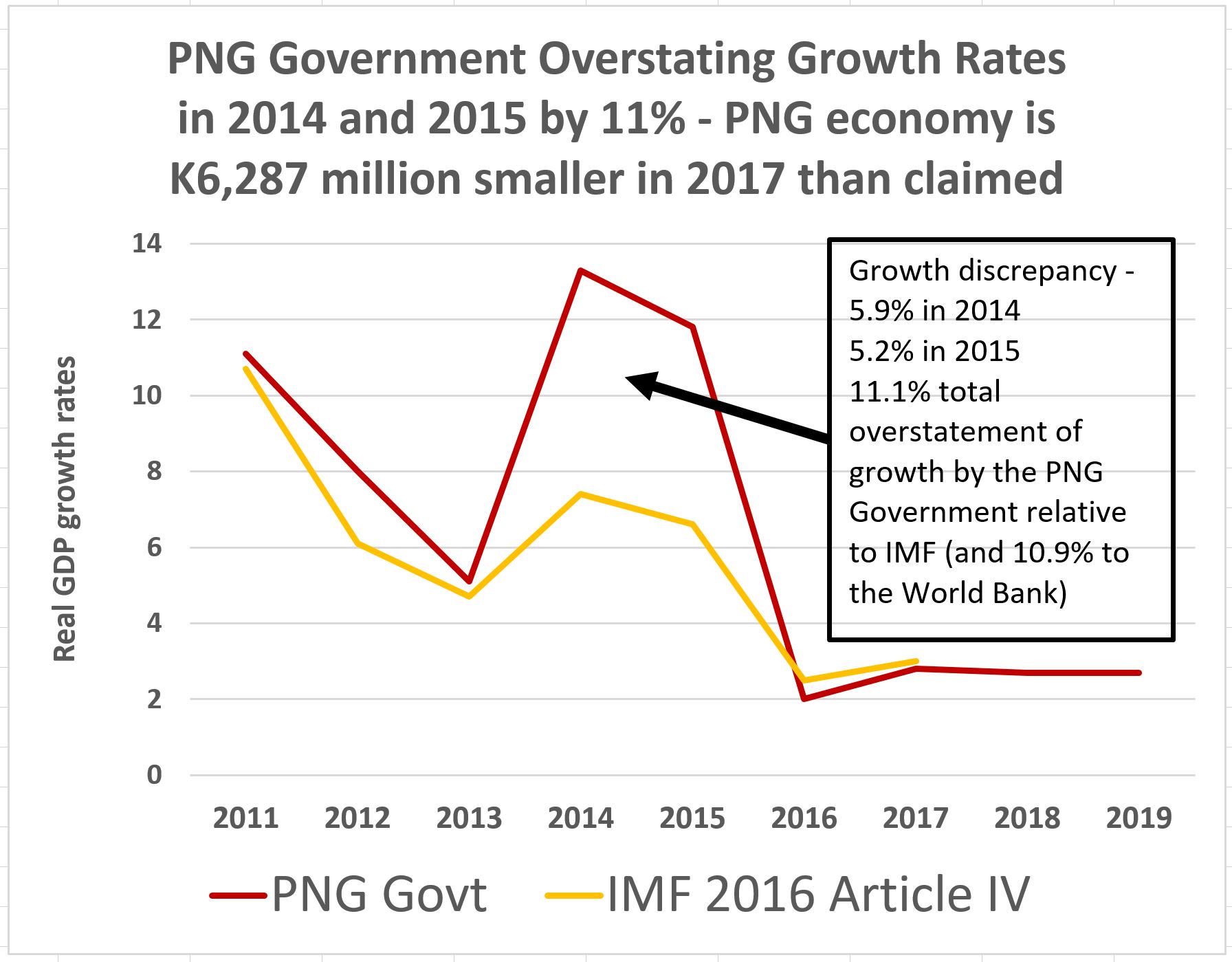

The deficit has increased from K524m in 2012 to K3,086.9 million in 2016. The FBO reports this is 4.6% of “new” GDP but the IMF indicates the “new” GDP numbers are significantly overstated (a report that still has not received any factual coverage in the PNG media on issues such as the PNG government exaggerating economic growth rates by 11.9 percentage points – see here).

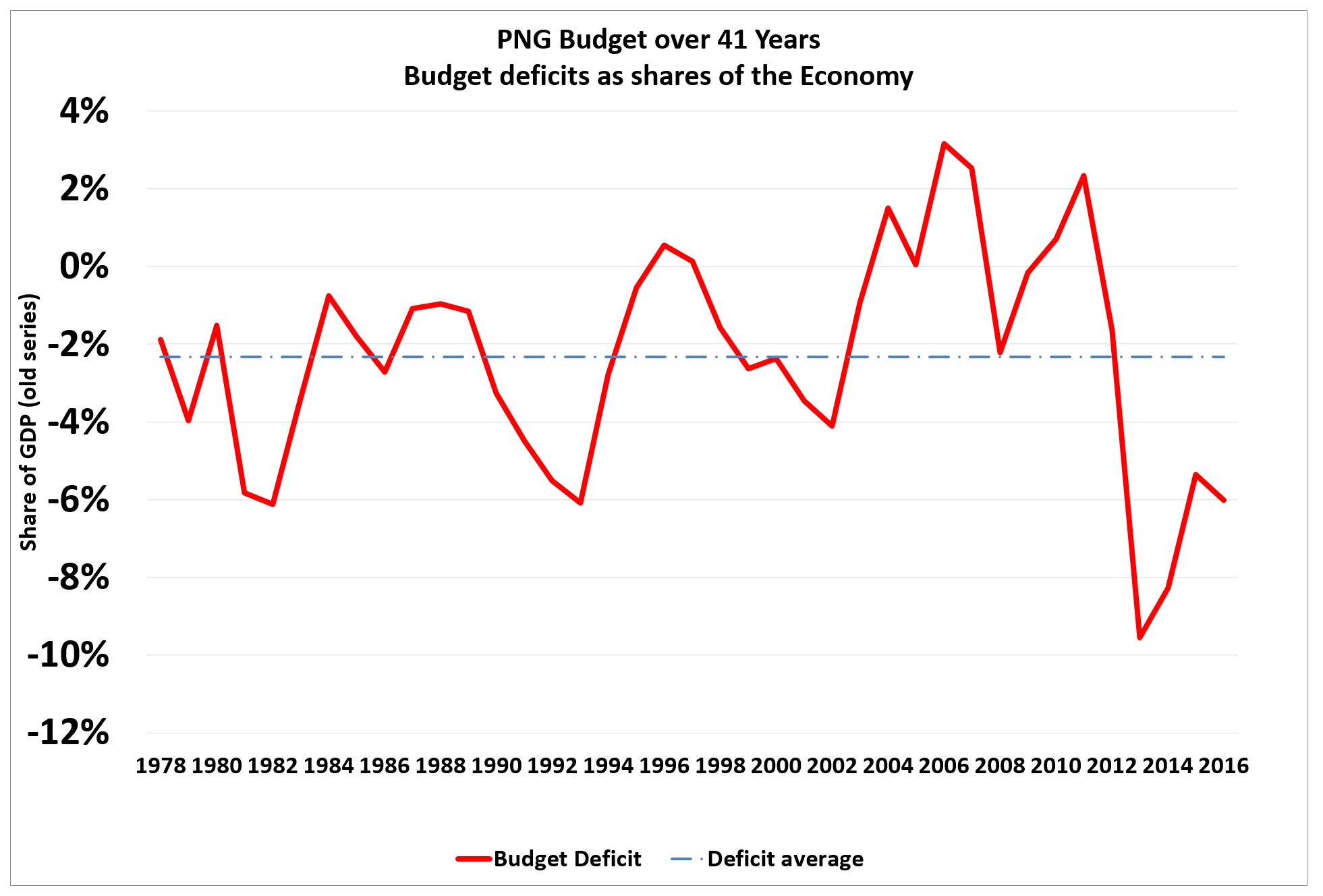

To allow historic comparisons, and for consistency, most of this blog will be based on the “old” GDP series (one that was still used in many parts of the 2017 Budget including its key GDP table) . In terms of these “old” GDP figures, the deficit has increased from 1.6% in 2012 to 6.0% in 2016.

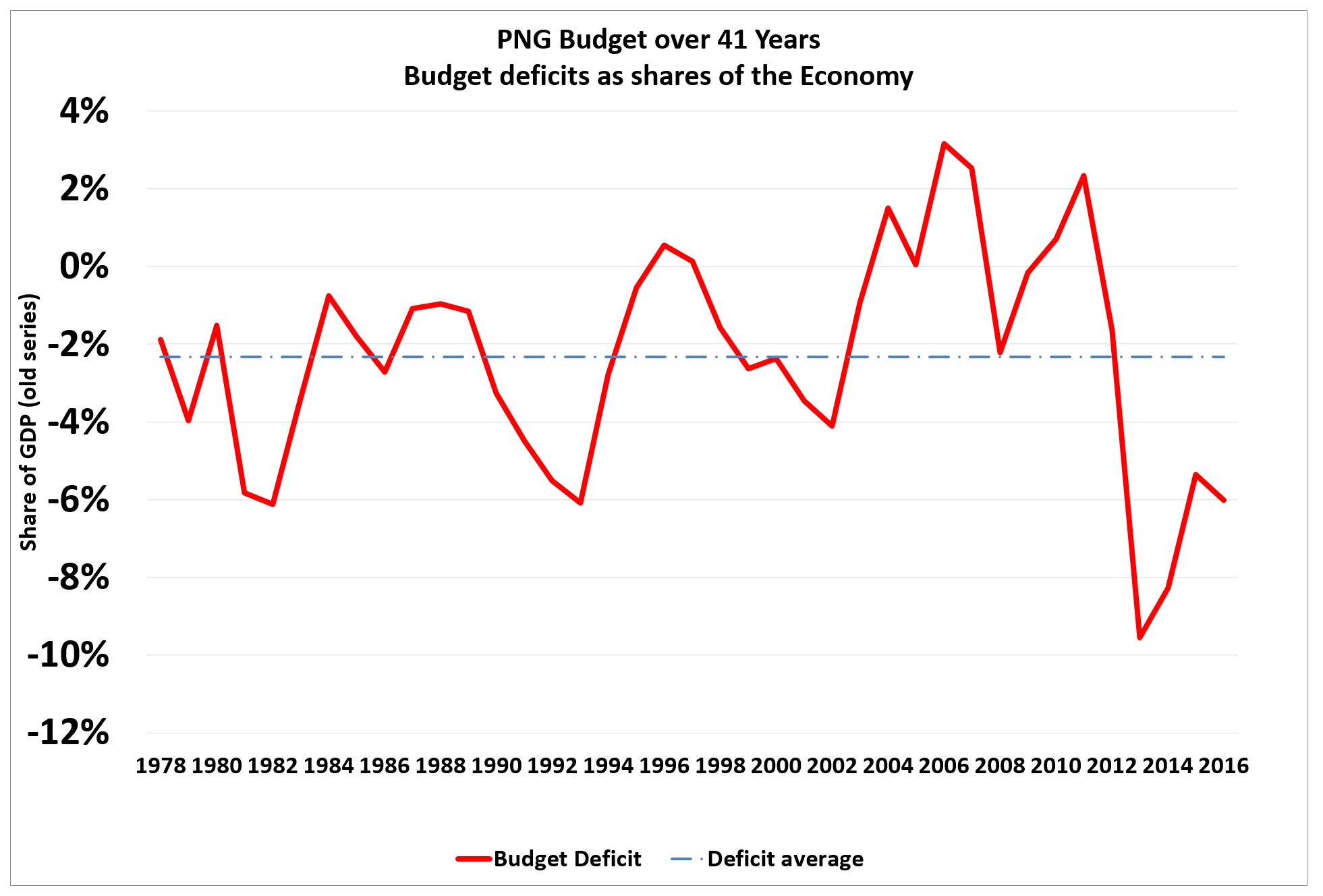

The following graph shows PNG’s budget deficits since independence. The average deficit figure has been 2% – so the 2016 budget outcome is three times greater than usual. Since 2012, PNG has moved to the most sustained and serious pattern of deficits since Independence. With the deficit increasing again, the path to fiscal recovery is very unclear.

(Source: Budget documents for deficit figure. Use of old GDP series to allow for historic comparisons as the “new” series is both overstated according to the IMF and only has been backdated to 2006).

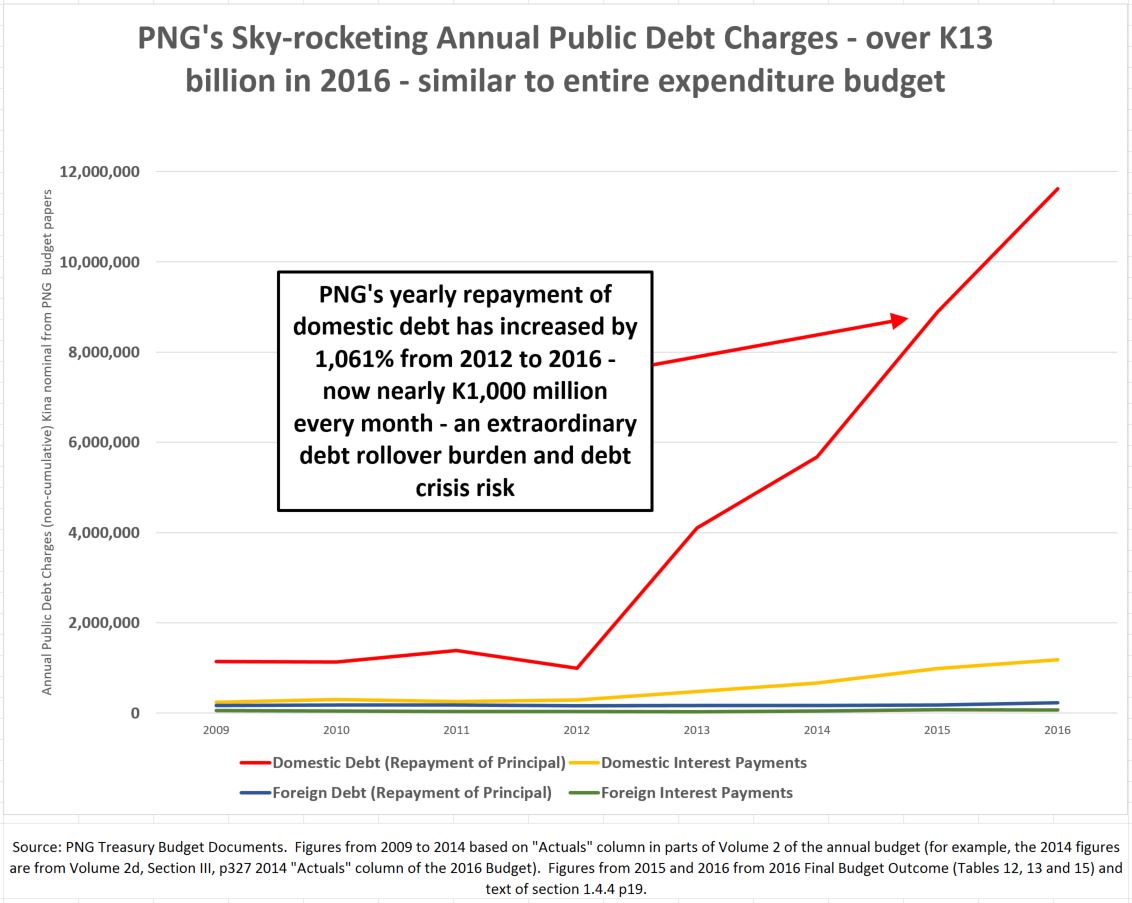

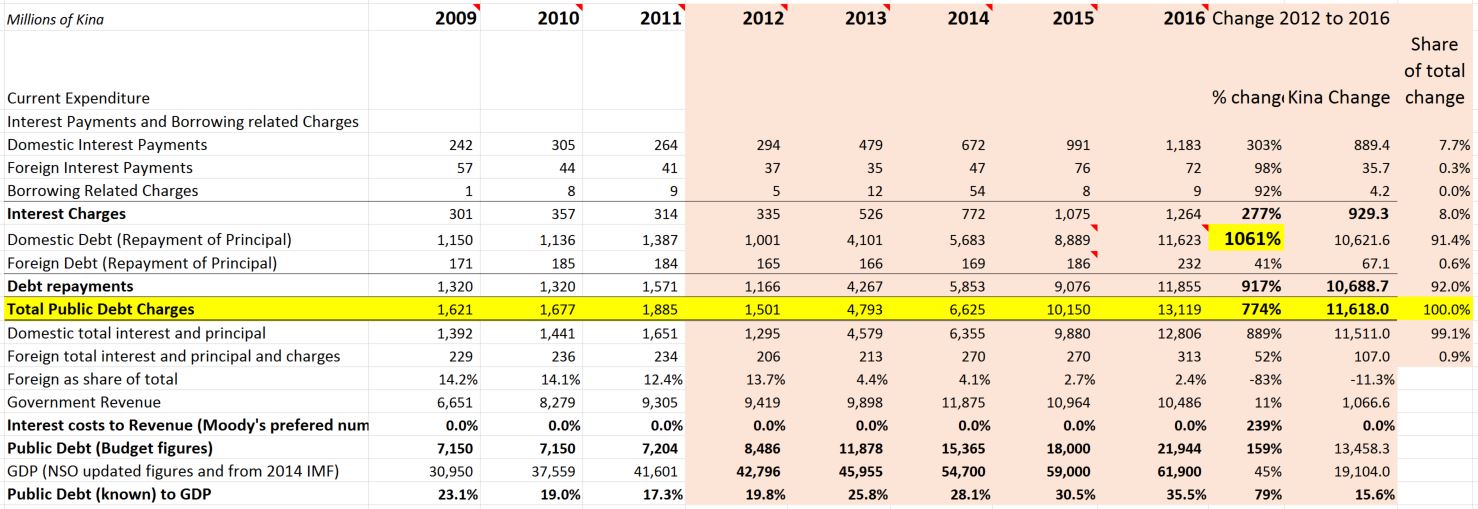

This pattern of large deficits has led to a blow-out in debt. PNG public debt levels (so ignoring off-budget debt held in SOEs such as the UBS loan for Oil Search shares) has increased from K8, 486m in 2012 to K21,944m in 2016. As a share of GDP, it has increased from 26.9% to 42.7% (using the ‘old’ Treasury GDP numbers for consistency – using IMF figures, the number is 35.5%).

PNG has already exceeded the public debt level expected at the end of 2017.

PNG’s public debt is now 258% of its 2012 level. This will be a painful legacy for PNG’s future as little of the debt blow-out has been properly invested.

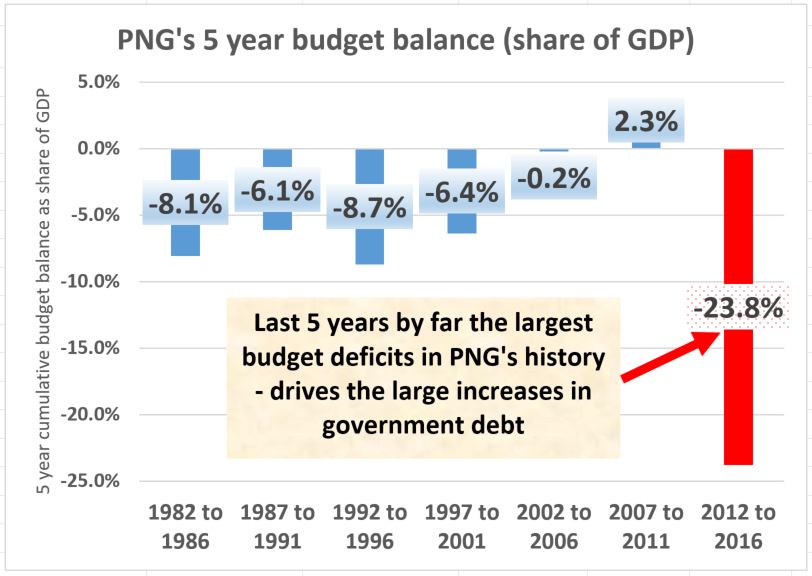

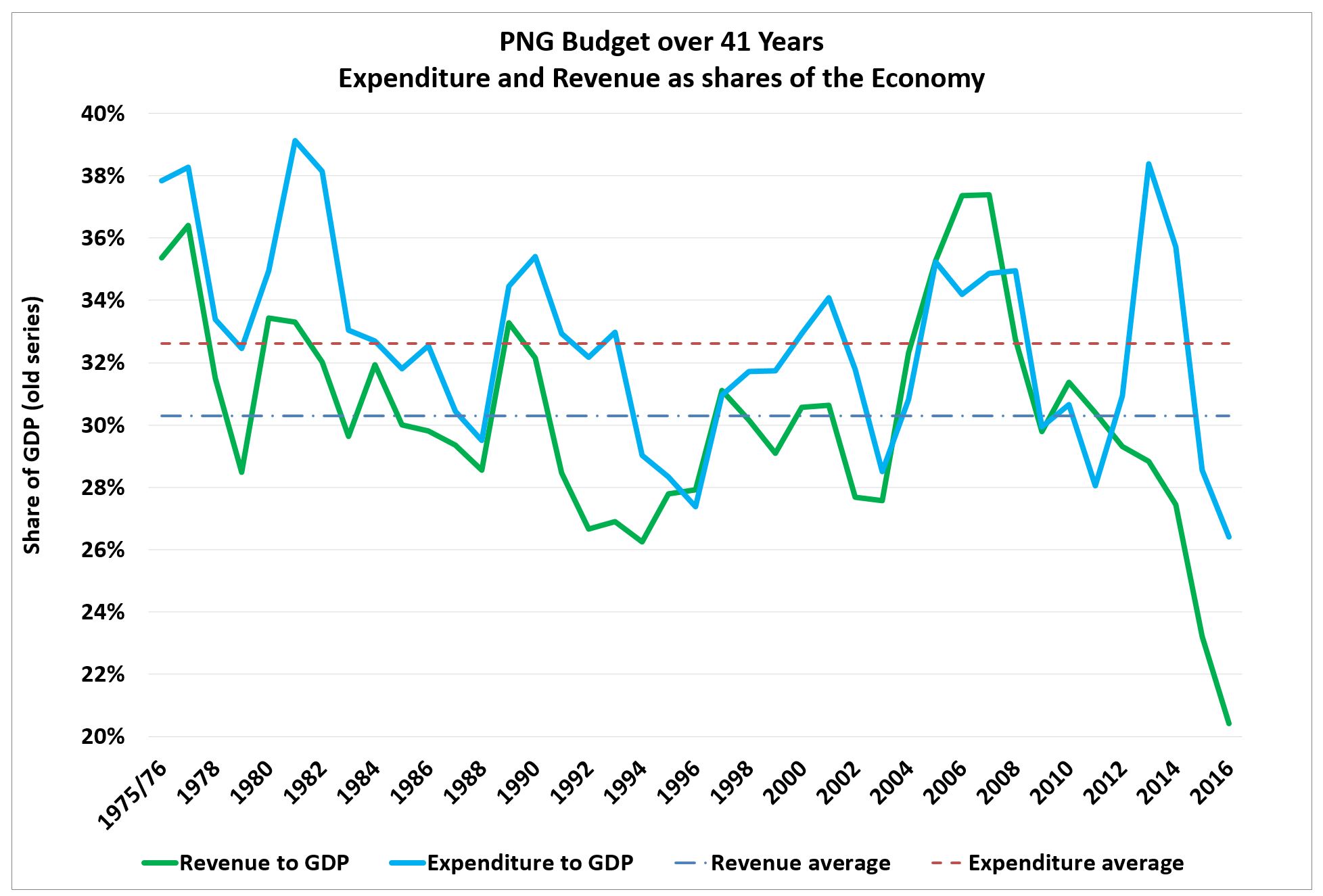

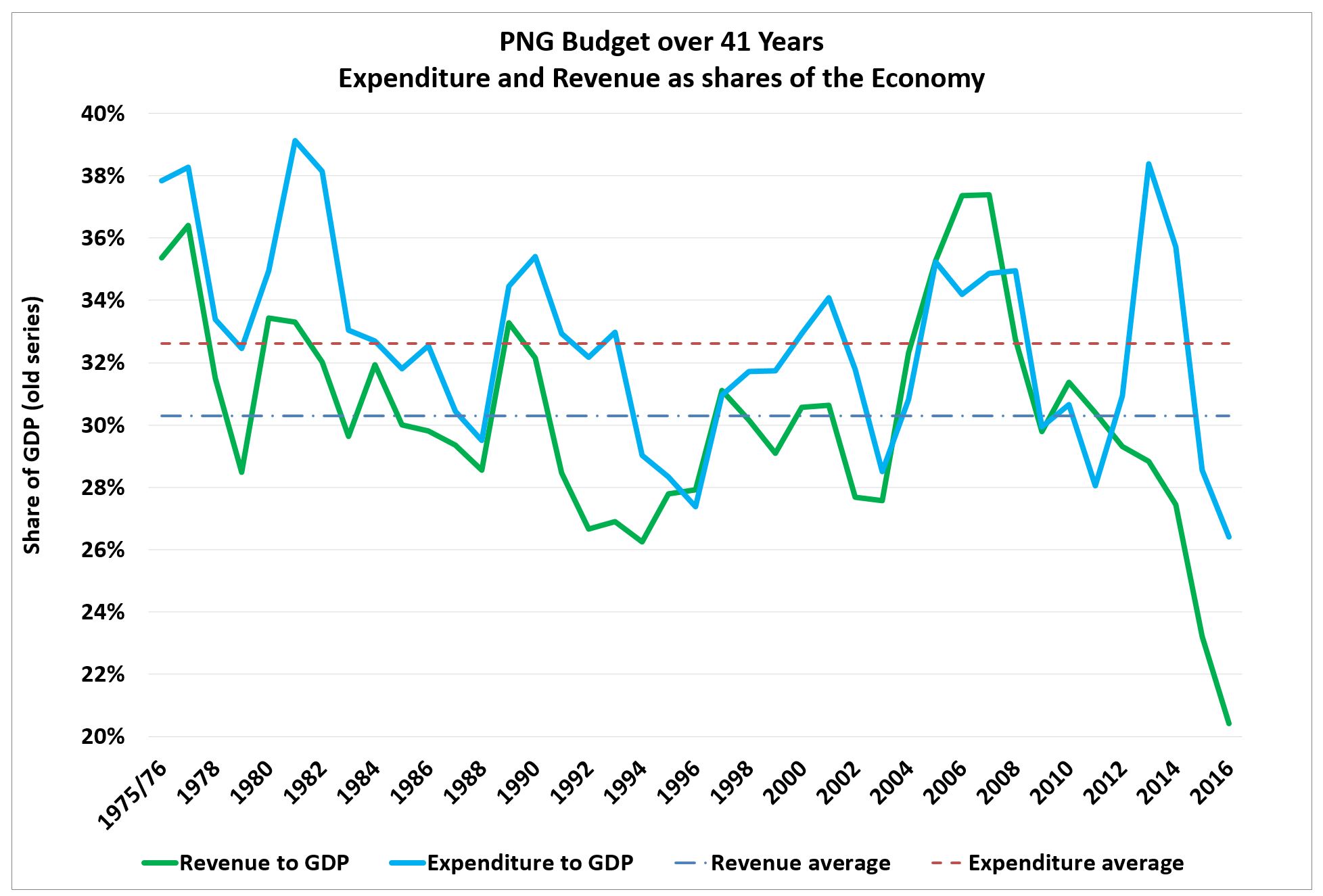

The reason behind PNG’s huge deficits is analysed in the following graph. The deficit is the difference between government revenues (shown by the green line) and government expenditures (shown by the blue line). These are expressed as shares of GDP to provide a historic perspective. There are two key features of this graph.

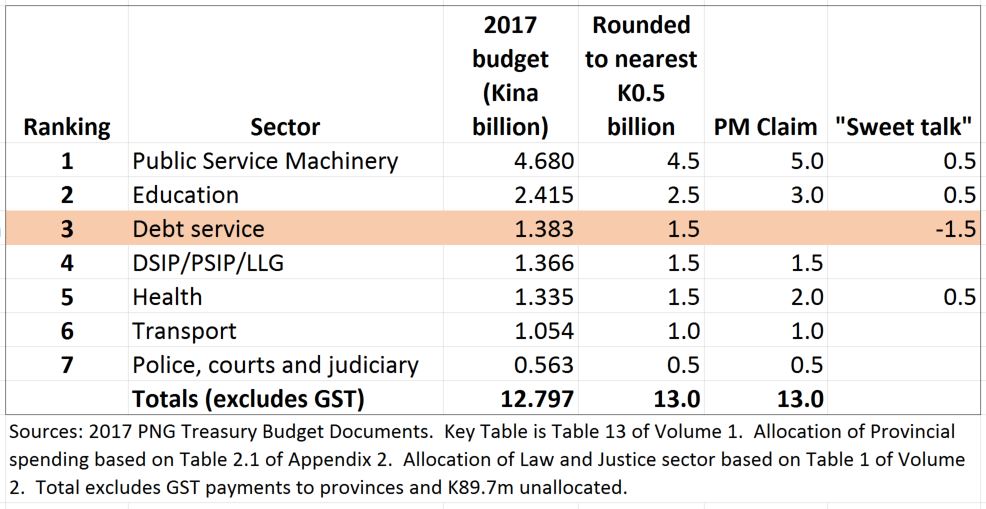

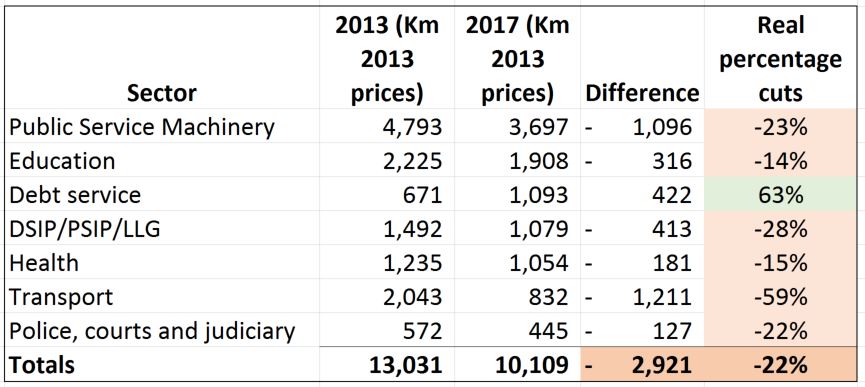

First, the expenditure expansion in 2013 by the O’Neill government was unprecedented in PNG’s history. Many of the government’s commitments were very expensive – such as the move to district financing through MPs as well as giving parents’ an effective tax cut by abolishing tuition fees. These expenditure commitments were made before income was received – counting the chickens before the eggs had hatched. From 2015 (after a delayed response) PNG has embarked on severe expenditure cuts – more severe than those imposed on Greece. Earlier articles – see here and here – indicate that the majority of these cuts, contrary to government claims, have been in the key areas of education, health and infrastructure.

The second striking feature of the graph is the collapse in revenues. Revenues have never been so low as a share of the economy. Previous posts have demonstrated (see here) that the main reason for this is not the fall in international commodity prices but because of the weakness in the overall economy of PNG and a diversion of dividend funds to Kumul Petroleum (rather than through the Sovereign Wealth Fund and back into the budget). This is the key areas of budget repair that has been ignored by government – there is a need to do something to fix the collapse in revenues. The Sir Nagora Bogan tax report provided a possible roadmap for recovery and improving economic efficiency. The low level of taxation of the resource sector – including logging – is a major issue that should be addressed to help restore some of the severe cuts to health and education.

The FBO confirms further major reductions in personal and company income taxes reflecting the current weakness of the PNG economy. The FBO also effectively admitted that the government was partially responsible because of its poor management of foreign exchange – “Foreign exchange imbalance also dampened business activities thus lower tax revenues” (sic) – page 8 of FBO.

And as even the Treasurer has pointed out, from 2016 onwards, economic growth rates of 2 to 3 per cent are lower than the population growth rate – so income per capita is forecast by the PNG Treasurer and PNG Treasury to keep falling over the next four years. PNG is going backwards economically – and this situation is expected to continue for years.

There is no practical vision for getting PNG back onto a development path. As the PNG LNG project has indicated, it would be foolish for PNG to put much belief in the hope that the resource sector can transform life on the ground for most Papua New Guineans.

The composition of expenditure cuts points to very poor budgeting and planning systems. In particular, the government indicated in its supplementary budget that it would be cutting expenditure by K928m for the remainder of 2016. In the end, the cuts amounted to only K262.2m. Staffing costs actually exceeded the Supplementary Budget by an extraordinary K471.0 million. Some deeper analysis of Appendix D in the FBO indicates most of this was for teacher salaries where the Supplementary Budget figure of K1,023 million was exceeded by K317.6 million. Such a massive difference of 31% in such a large and key area points to a lack of planning ability. The Tuition Fee Free Education policy was inevitably going to require more teachers and the government knew that teacher salaries were being increased – but such obvious costs did not flow through to the budget. This is poor management.

As usual, there are some hidden gems in such budget reports. For example, Table 33 on the K100 million spent through the “Secretary’s Advance” by Dairi Vele included K1,608,400 “to settle bills for Javati/Twivey Lawyer” and a rather unusual K18 million paid by the Electoral Commission to the Washington Embassy.

The performance information in Appendix 3 for many major projects (apart from those on road infrastructure) are difficult to reconcile. For example, the first item called “Provincial Hospitals Infrastructure” project is rated as 70% complete and operating to standards. However, this project expected to receive K225 million in 2016, this was severely cut to K160 million in the Supplementary Budget, and only K23 million was actually provided. How did this project complete 70% of its activities with only 10% of the expected budget? Such dubious performance reporting undermines other claims by government that it is achieving its Alotau Accord targets

Going forward, the extent of changes between the 2016 FBO and the 2016 Supplementary Budget has significant implications for the 2017 Budget. In particular, the Supplementary Budget assumed that revenues would increase by K928m but the FBO indicates revenue actually fell by K1,236.7 million – a difference of K2,164.7 million. Some of these lower revenue numbers, in particular the lower tax revenues, will flow into lower revenues in 2017. Likewise, some expenditure areas will be much higher than indicated in the 2017 budget. The starting base for staffing costs is now K471.1 million greater than expected and the government has shown no ability to curtail staffing costs. The K1,102.7 million reduction in goods and services expenditure late in 2016 as part of the close of accounts process could also partially represent simply a deferral of bills. Some of these bills will now have to paid in 2017 or defaulted on by the government – at the risk of hurting businesses and others owed money.

There is little doubt that the 2017 budget is now significantly off-track and a much larger deficit is inevitable. The 2017 budget needs to be redone.