There will be hundreds of people looking to do an analysis of the budget and what it means for the future of PNG.

Following is a 10 point guide from someone that started analysing PNG’s budgets back in 1978 and once used to be able to get into the media lock-up (but can’t now as I’m banned from the country).

1. Be prepared

The 2019 Budget needs to be looked at in comparison to recent budget documents and reports. So bring along at least electronic copies of the 2018 Budget, the 2018 MYEFO, the 2019 Budget Strategy (all available from the Treasury website) as well as the 2018-2022 Medium Term Development Plan (available from the National Planning Website). This is just useful for checking if the budget is doing what the government said it would be doing.

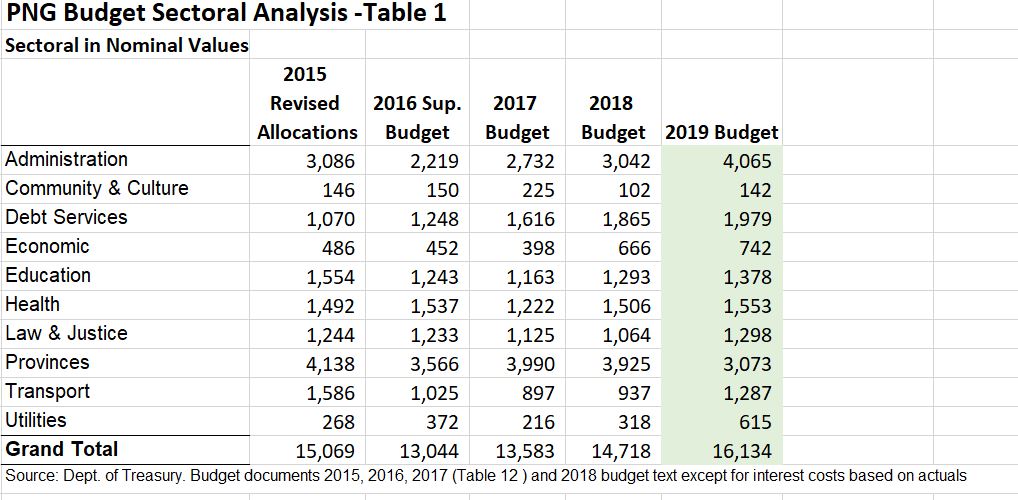

Also bring along the latest figures from respectable outsiders – so the latest figures from the IMF and World Bank are probably most pertinent. The latest World Bank and IMF’s analysis of the PNG economy is included in the following document as part of its assessment for providing budget support, including the agreed actions for the $US150 million in support – available here. The latest IMF Article IV report is also helpful, as is the UPNG/ANU PNG draft economic survey – available here.

2. Don’t start reading the words – start with the numbers.

This may sound strange, but I always recommend that you start with Budget Volume 1, go to the last Annex (about page 120 or so) and begin with Table 1 titled “Gross Domestic Product by Economic Activity” – or GDP for short. It is an attempt by economists to measure the size of the economy.

This is the first fundamental test of the credibility of the budget, and therefore any of the words in the budget speech and Executive Summary. Table 1 has lots of interesting information for economists and industry analysts, but for budget analysis the key figures are at the bottom of the table – what is the government saying is the size of GDP and how quickly is it growing?

Following is a quick table with recent previous estimates of GDP – this guide will have some tables where 2019 Budget figures can be inserted (usually in the green sections) and then compared with what the outside experts are saying (and these experts get to have a good look and sometimes actually even operate the relevant background models in PNG Treasury).

| Nominal GDP (Kina Billions) |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

| IMF – bottom of page 54 except for 2013 figure from 2017 IMF Article IV) |

47.7 |

56.8 |

57.1 |

59.3 |

63.8 |

68.0 |

71.7 |

75.5 |

80.5 |

85.9 |

|

| PNG National Statistics Office |

47.7 |

56.7 |

57.1 |

na |

na |

na |

na |

na |

na |

na |

|

| 2018 Budget |

47.7 |

56.6 |

62.2 |

67.8 |

73.9 |

80.1 |

85.9 |

92.2 |

99.1 |

107.0 |

|

| 2018 Budget Strategy |

|

|

|

|

75.6 |

81.9 |

86.9 |

92.9 |

100.2 |

108.9 |

|

| 2019 Budget |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

First, it can indicate if some games are being played – especially if there are big differences between what the PNG government says, and what its own National Statistics Office and outside agencies say. For example, we know that everyone agreed essentially on the size of the PNG economy in 2013 and 2014. There has been agreement that the NSO figures once produced are the most accurate available and should be used (they actually work with the Australian Bureau of Statistics to produce these figures). However, the National Statistics office released in March 2018 a new estimate for the size of the economy in 2015 which was substantially lower than the PNG Treasury’s. The World Bank and IMF use this new NSO estimate. This new GDP estimate for 2015 should have been used in the 2019 Budget Strategy but it wasn’t. This then produces very big gaps between what the IMF and World Bank estimate as the likely size of the economy, and what the PNG government claims – a gap that continues to grow. Hopefully, the 2019 Budget will use the 2015 GDP figure estimated by the National Statistics Office. If not, the budget fails the first sniff test.If there are big differences between what the IMF/World Bank estimate – top line – and the 2019 estimates, why does this matter?

GDP ends up affecting the budget in three important ways.

First, many of the fiscal responsibility ratios are based on GDP as the base. For example, the debt to GDP ratio is not supposed to exceed 35%. If you have a bigger GDP number, it means you can have more debt without breaking the law. Likewise, the fiscal deficit number is expressed as a share of GDP – so a bigger GDP means your deficit figures look better when put in terms of “% of GDP”. Big increases in expenditure look more reasonable if expressed as a percentage of rapidly growing GDP. An example of this effect is given below which provides the level of public debt, and then expresses it as a percentage of GDP. The bottom row using current 2018 Budget and 2019 Budget Strategy figures for public debt, and dividing them by the World Bank/IMF/NSO GDP estimates, shows the Fiscal Responsibility Act actually has been breached since 2016 (so figures greater than 35). This is a very different result than the figures used in the 2018 Budget and 2019 Budget strategy. Will this change in the 2019 Budget?

| Government Gross Debt Kina Billions |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

| Implied figure from IMF’s GDP and debt to GDP ratio – interestingly a bit lower govt |

11.9 |

15.4 |

18.4 |

21.9 |

23.5 |

24.5 |

25.8 |

27.0 |

28.6 |

30.2 |

|

| 2018 Budget Vol 1 Ann 3 Table 15 |

|

|

18.0 |

21.9 |

23.8 |

25.8 |

27.7 |

29.4 |

30.8 |

32.1 |

|

| 2018 Budget Strategy Table 3 p13 |

|

|

|

|

|

25.8 |

27.4 |

29.1 |

30.5 |

31.8 |

|

| 2019 Budget |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Government Gross Debt Share of GDP |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

| IMF/World Bank page 54 for 2014-22 and IMF Article IV for 2013 |

24.9 |

27.1 |

32.2 |

36.9 |

36.9 |

36.1 |

36.0 |

35.8 |

35.5 |

35.2 |

|

| 2018 Budget Vol 1 Ann 3 Table 15 |

|

|

29.0 |

32.4 |

32.1 |

32.2 |

32.2 |

31.9 |

31.1 |

30.0 |

|

| 2018 Budget Strategy Table 3 p13 |

|

|

|

|

|

32.2 |

31.8 |

31.6 |

30.8 |

29.5 |

|

| 2019 Budget |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Memo item – implied debt ratio using PNG govt debt figures and IMF/WB GDP figures |

|

31.5 |

36.9 |

37.3 |

37.9 |

38.2 |

38.5 |

37.9 |

37.0 |

|

| Re-calculate new 2019 Budget Public Debt Figure using NSO/IMF/World Bank GDP numbers (so public debt figure divided by actual GDP figure as a percentage) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

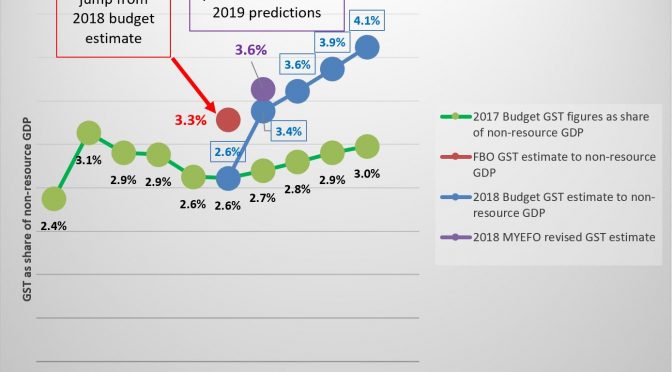

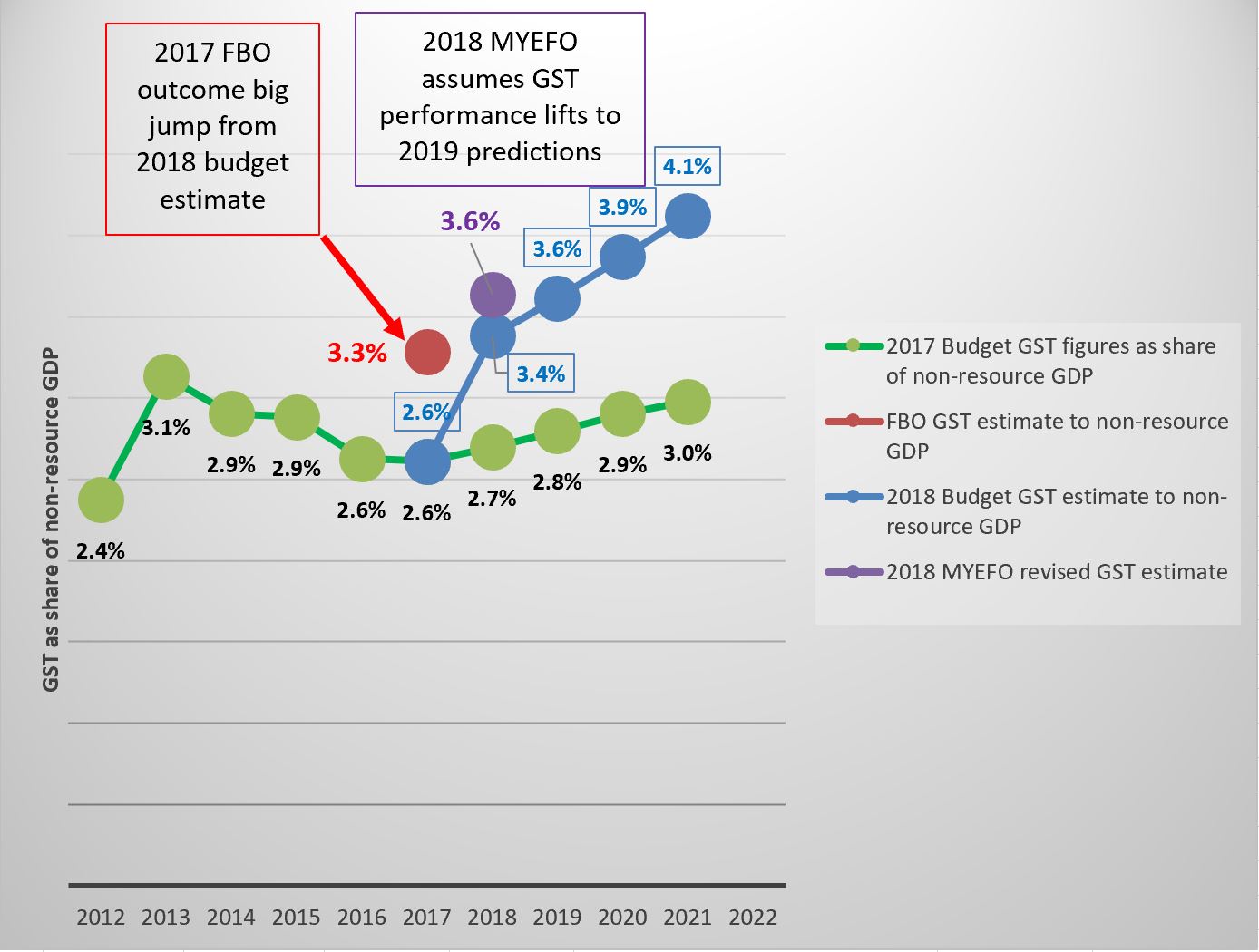

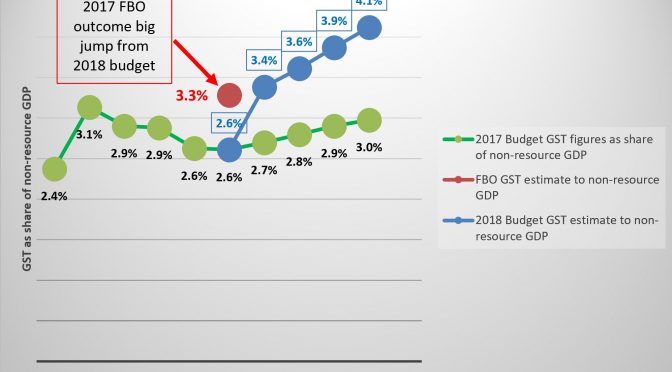

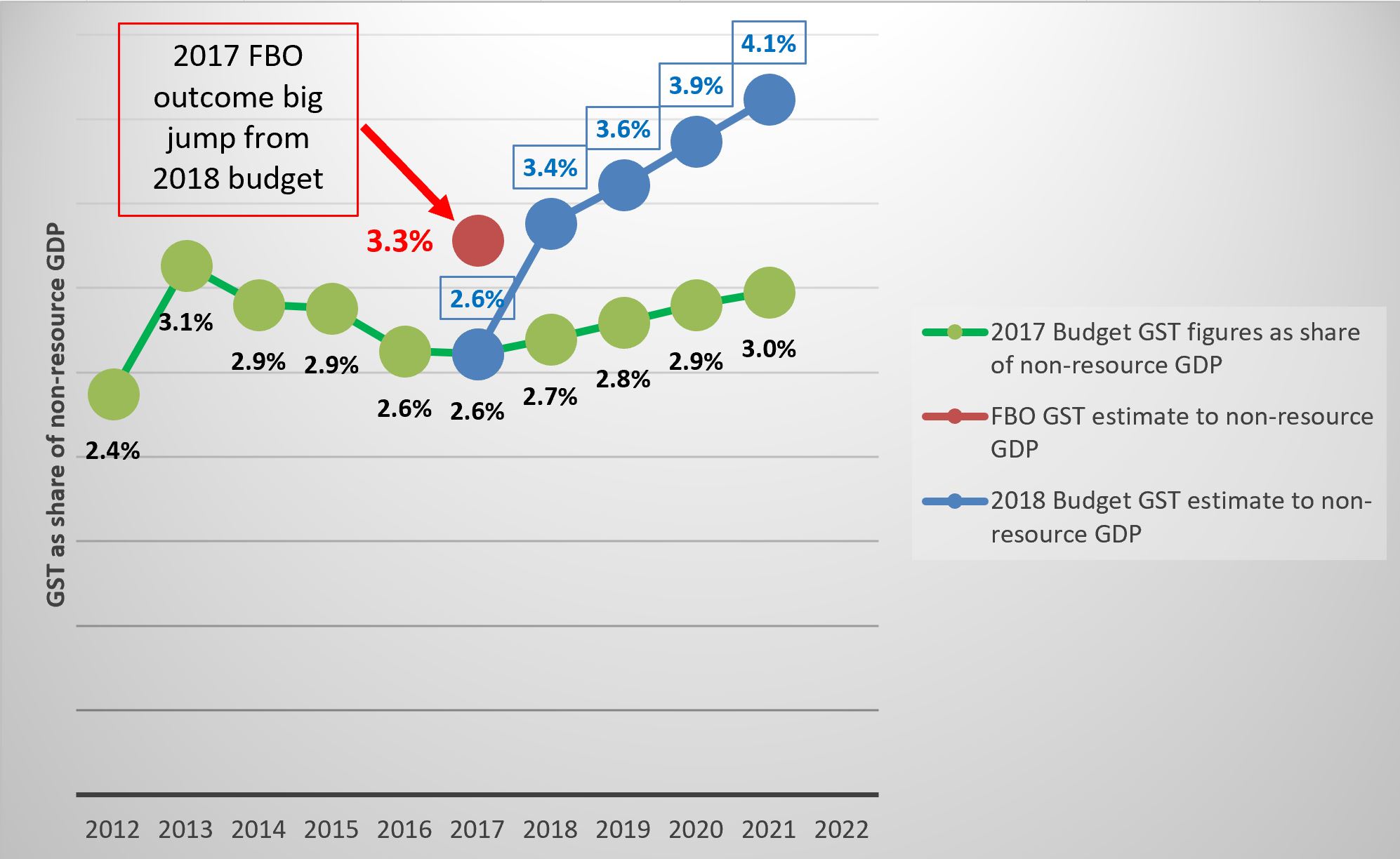

Second, revenue forecasts depend critically on nominal GDP forecasts. This is because the major sources of tax revenue are linked to parts of the measure of GDP – so wage income (the personal income tax), business income (company tax), the level of consumption (the GST) and various import and export taxes. Without changes in tax policies, there is often a near direct link – so assuming wage income is 20% higher probably means personal income taxes will be 20% higher (and possibly a bit more given bracket creep). So if the GDP number is too big relative to realistic forecasts, it probably means that revenue forecasts are also too high. If expenditure stayed at the same level, then we would expect that lower revenues would then lead into bigger deficits. So getting the GDP number seriously wrong probably means your entire fiscal strategy over the next few years will also be seriously wrong. So over-estimating GDP can lead to much bigger deficits and loose expenditure policy; under-estimating GDP can lead to smaller deficits and paying debt off more quickly.

Third, the GDP growth figures can provide another benchmark on how the economy has been going and the expectations of the government on how growth will perform in the future. Clearly, a negative number indicates a recession, and things are going badly. A very high number can also indicate excessive optimism. If there are very high growth numbers, are there very sound reasons for them? The usual approach, based on the experiences of PNG’s history and those of other countries, is not to bet on extremely high growth rates. For high growth rates push up the expected levels of revenues, which means that government’s can be tempted to plan to spend too much, which then pushes up debt and can trigger a boom/bust cycle. The best measure of PNG’s economic living standards are based on non-resource GDP (as most of the resource sector is foreign owned) after allowing for inflation – this is called “real non-resource GDP”. Real GDP figures are also useful. Negative numbers indicate a recession. Figures for both measures are shown in the following tables. The 2019 Budget Strategy growth figures started pushing the edges of credibility, especially by 2022 for non-resource growth. Will the 2019 Budget use more realistic growth assumptions?

| Real Non-Resource GDP growth rates |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

| IMF/World Bank page 54 for 2014-22 and IMF Article IV for 2013 |

3.6 |

7.0 |

-3.1 |

-0.1 |

1.9 |

1.4 |

1.9 |

2.3 |

2.8 |

2.9 |

|

| 2018 Budget Vol 1 Ann 3 Table 1 |

3.6 |

3.3 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

1.9 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

|

| 2018 Budget Strategy Table 2 p11 |

|

|

|

|

0.2 |

2.8 |

2.9 |

4.2 |

5.0 |

6.9 |

|

| 2019 Budget |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Real GDP growth rates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| IMF/World Bank page 54 for 2014-22 and IMF Article IV for 2013 |

3.8 |

15.4 |

5.3 |

1.6 |

2.5 |

-1.6 |

3.5 |

3.1 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

|

| 2018 Budget Vol 1 Ann 3 Table 1 |

3.8 |

12.5 |

10.5 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

2.4 |

2.2 |

2.0 |

2.5 |

2.8 |

|

| 2018 Budget Strategy Table 2 p11 |

|

|

|

|

3.0 |

1.0 |

2.3 |

3.0 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

|

| 2019 Budget |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Stick with the numbers – you can tell I’m a number person!

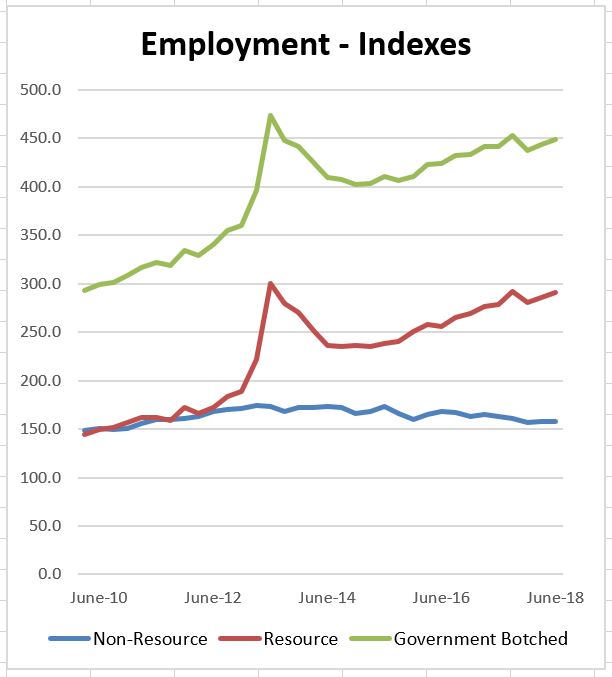

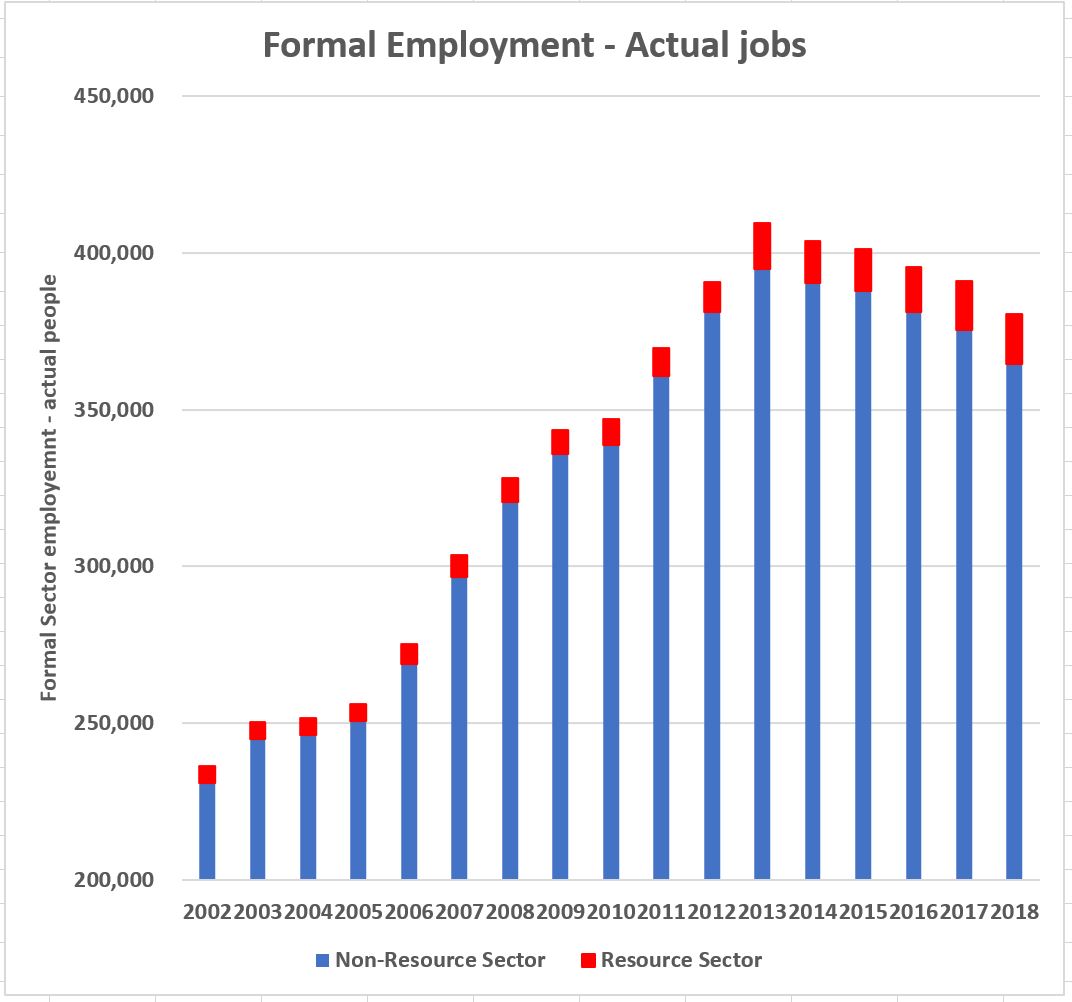

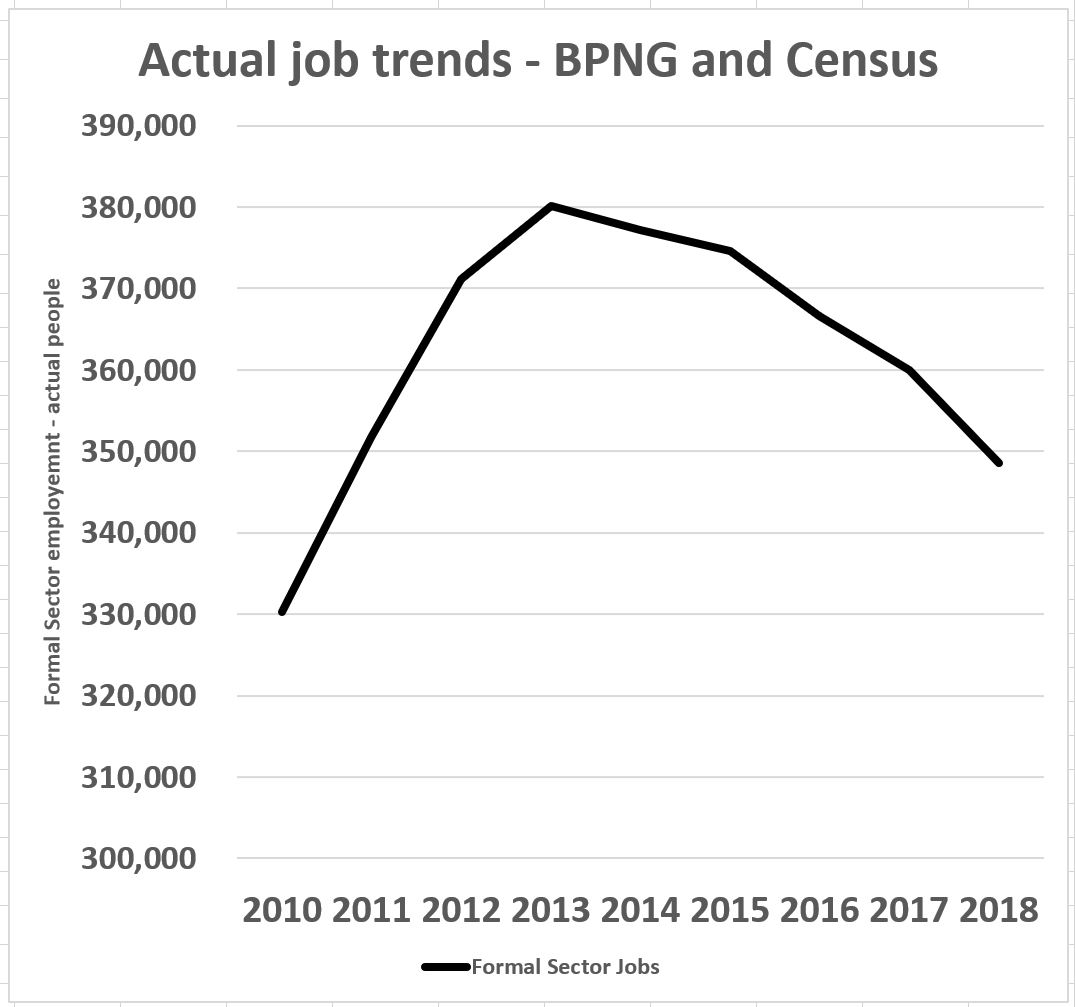

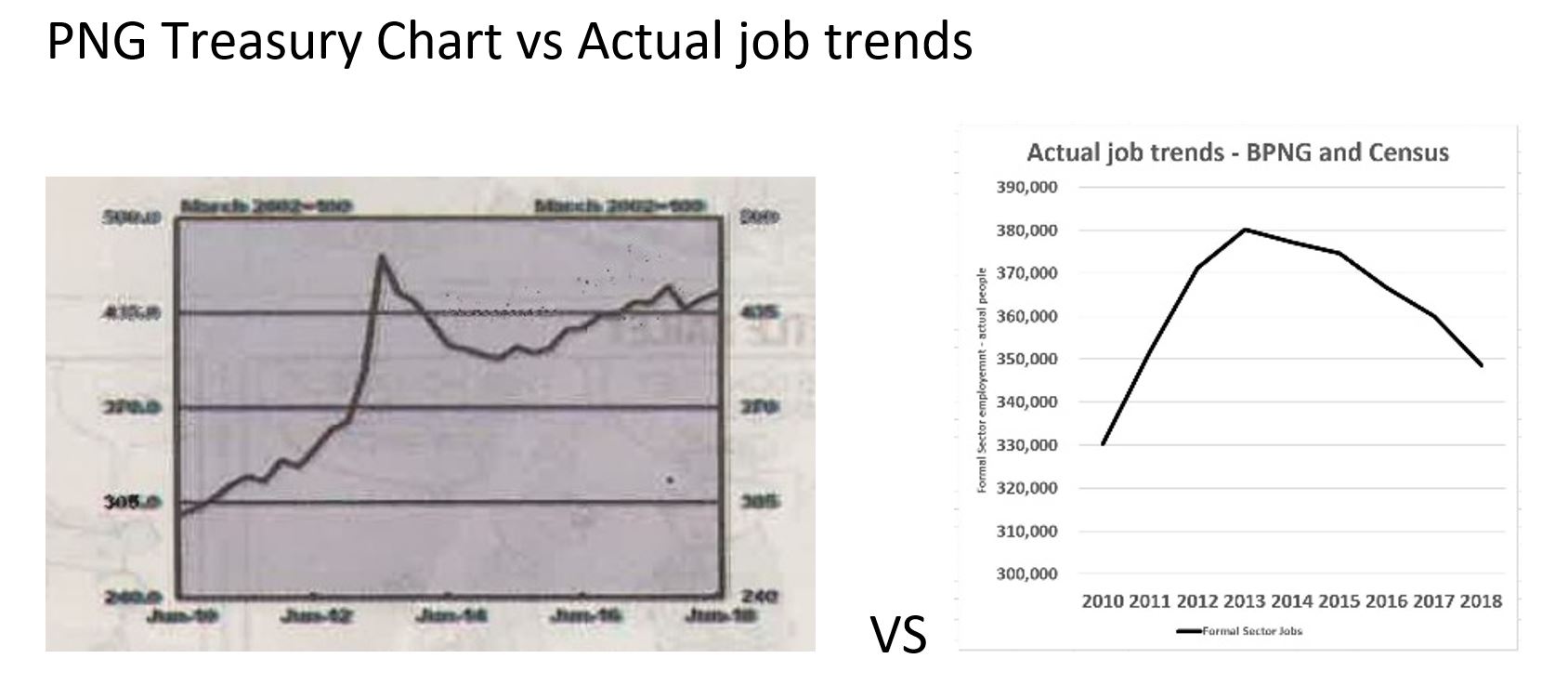

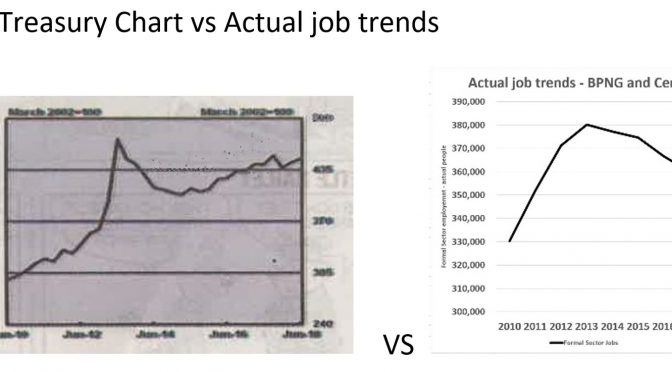

Have a quick look at Table 7 in this back of the budget annex on formal sector employment. Hopefully the non-mineral employment index would have moved back to at least its level of 172.2 in 2013 – its been falling in recent years.

Have a quick look at Table 8, especially the line on “Credit to the Private Sector”. This hopefully will be well above the expected rate of inflation – otherwise a sign of a lack of investment in the economy. Unfortunately, this went backwards even before inflation in 2017, and the World Bank and IMF expect it will go backwards again in 2018 by another 4.3 per cent before a modest recovery in 2019. This is hard to explain as the earthquake would have been expected to increase investment rebuilding, as well as some APEC-related work.

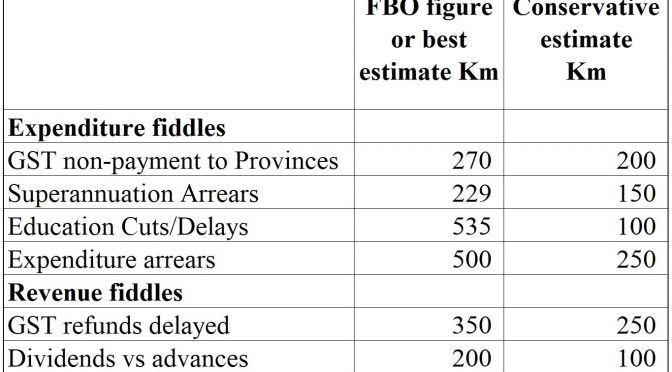

Now to Table 10 called “Statement of Operations for General Government”. This table is absolute gold! As long as it is accurate (there were big errors in the 2018 budget between Annex Table 10 page 138 and Table 6 on page 33 but hopefully this won’t be repeated in 2019).

It gives you a wonderful overview of how things have been going on revenues, expenditures, key fiscal deficit ratios, financing and even a double check on the GDP numbers (the latter can vary between the various tables – Table 1 is the best source)

Actually, you almost don’t need to read anything else in the entire budget except for key announcements about any tax changes, expenditure initiatives and sectoral spending composition!

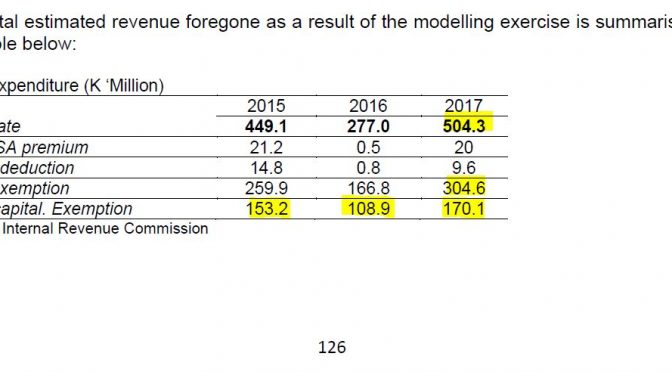

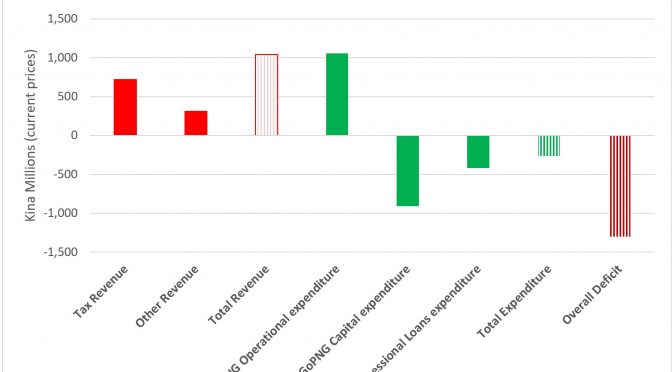

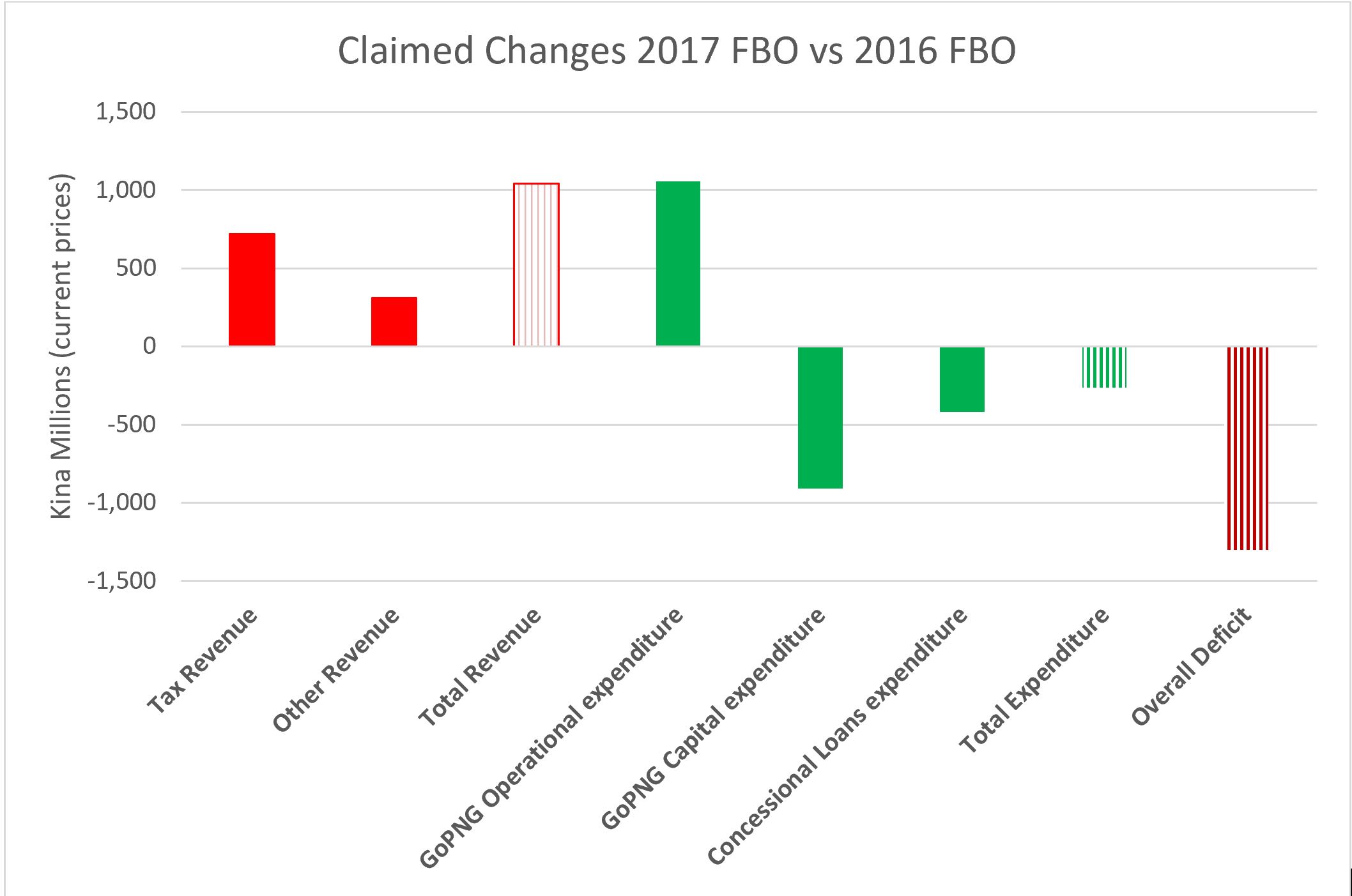

Given the boom in oil/LNG prices, it will be interesting to see how much of a tax windfall has been received from the resource sector in 2018, and if this is expected to continue. This is combined in the lines under ‘resource revenue’. Revenue as a percentage of GDP is also interesting, although World Bank will be looking more specifically at the tax to GDP ratio. The figures on Compensation of employees (payroll for public servants and teachers) is vital for seeing whether this largest category of expenditure is being bought under control. The line on interest costs is also interesting – has this been bought under control? There are then five measures of the difference between types of revenues and types of expenditures. Sounds boring, but this is actually the key budget policy reform that has been introduced by Treasurer Abel. So the focus used to be the “Net Lending/Net Borrowing” line. This is the difference between all revenues and all expenditures – it is the same number you need to borrow and impacts directly on public debt levels. It used to be the focus of looking at the fiscal deficit.

However, that is now old hat. The Treasurer has committed to the focus being on the “non-resource primary balance”. Indeed, the PNG Parliament agreed that this would be the new “fiscal anchor” for PNG’s budget strategy and has legislated that the aim is to have a zero non-resource primary deficit over the medium-term. So what is this new measure? Essentially, the aim is to de-link budget spending from the ups and downs of volatile commodity prices. This is done by excluding all resource revenues. The aim also is to focus on the current situation rather than problems from the past, so all interest costs are also excluded (this is the “primary” reference).

This then gets to probably the key issue in the entire 2019 budget in terms of fiscal policy. When the new government came to power and moved to this new fiscal anchor in late 2017 including having Parliament incorporate it under changes to the Fiscal Responsibility Act, interest costs were higher than resource revenues. This meant that the ‘non-resource primary balance’ was lower than the old fiscal deficit definition. This could give the impression that the government was planning to return to a budget surplus earlier than if the old measure was used.

However, and this is interesting, there is talk that resource revenues have absolutely boomed over the last few months. The government then had a choice. One option was to keep to the new fiscal anchor and save the boom in resource revenues by reducing public debt. That’s what they promised the World Bank and IMF when they received the budget support – it is the first point in their agreement. It’s what they indicated would happen in the 2019 Fiscal Strategy released just over two months ago. The other option was that they would spend the extra resource revenue. On the old measure, that would mean the fiscal deficit would stay about the same. On the new measure, it would mean the fiscal measure would blow out.

So in the middle of this table is actually the key story for the budget – continuing fiscal discipline around the new fiscal anchor, or spending as much as possible using the old definitions. Fiscal discipline or big spending – this will be revealed in this line on “non-resource primary balance”. The following table allows figures to be entered for both the level in millions of Kina, as well as percentage of non-resource GDP.

| Key Figures for 2019 Fiscal Policy Stance |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

| Non-resource primary balance Kina Millions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| IMF/World Bank – don’t give actual figures, just implied percentages |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2018 Budget Table 6 p33 |

|

|

|

-3253 |

-665 |

-592 |

-442 |

-193 |

-10 |

98 |

|

| 2018 Budget Strategy Table 3 p13 |

|

|

|

|

|

-592 |

-442 |

-193 |

-10 |

98 |

|

| 2019 Budget |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Non-resource primary balance (% of non-resource GDP) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| IMF/World Bank page 16 for 2014-22 |

|

-8.7 |

-4.7 |

-4.7 |

-1.9 |

-0.3 |

-1.1 |

-0.9 |

-0.6 |

|

|

| 2018 Budget Table 6 p33 |

|

|

|

-4.6 |

-1.2 |

-1.0 |

-0.7 |

-0.3 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

|

| 2018 Budget Strategy Table 3 p13 |

|

|

|

|

|

-1.0 |

-0.7 |

-0.3 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

|

| 2019 Budget |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The fiscal discipline/fiscal big spending outcome can also be confirmed by looking at the total expenditure figure between 2018 and 2019. The 2019 Budget Strategy said there would be an increase of a modest 2% or K238 million. How does the 2019 Budget actually perform relative to 2018? Is the expenditure increase more or less than K238 million?

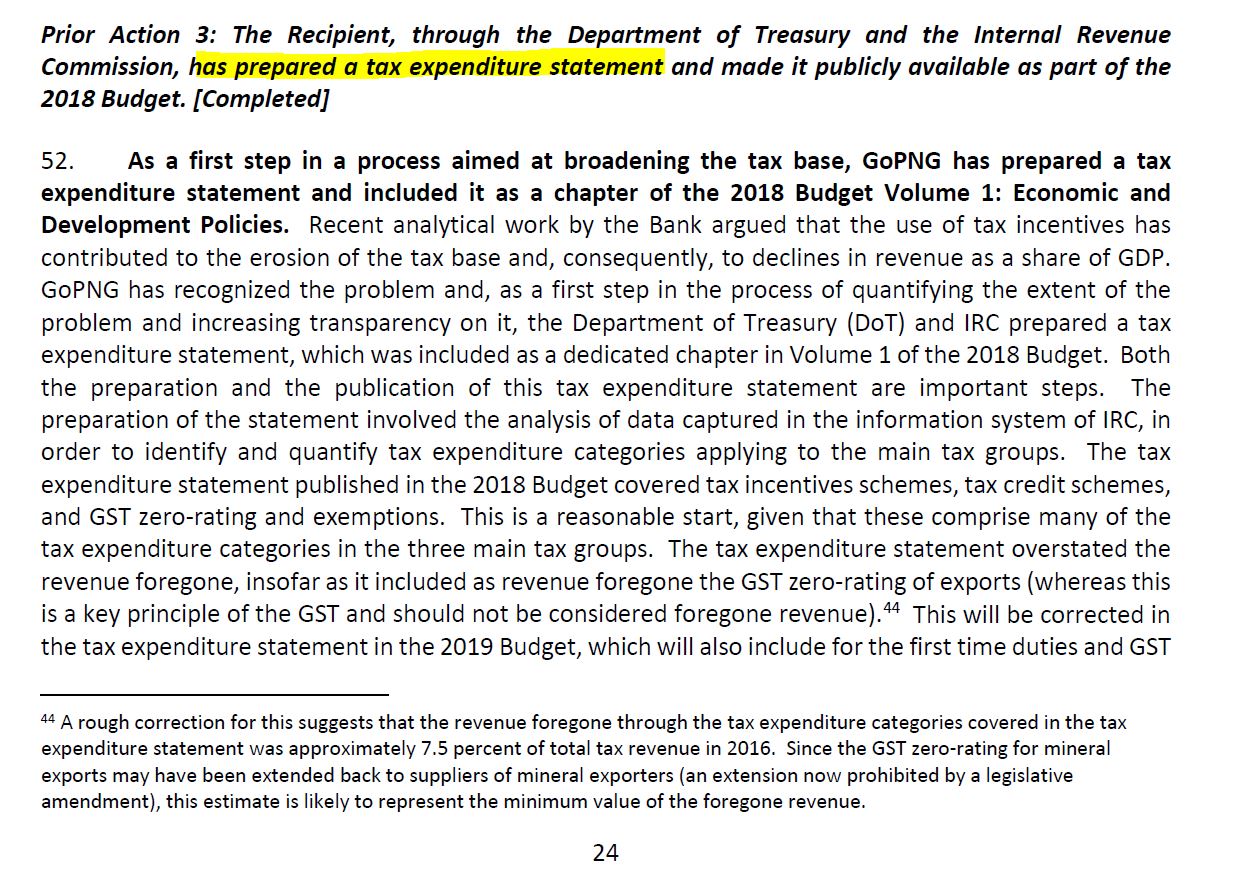

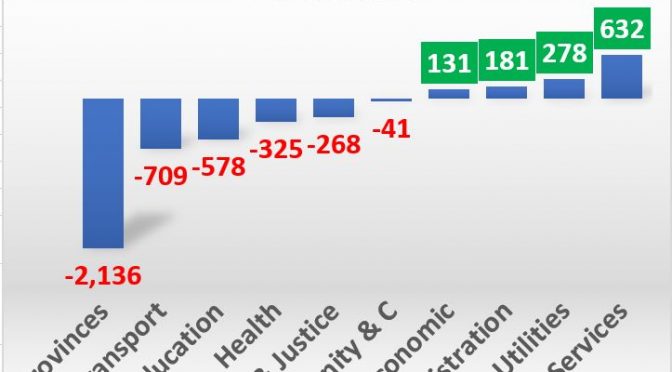

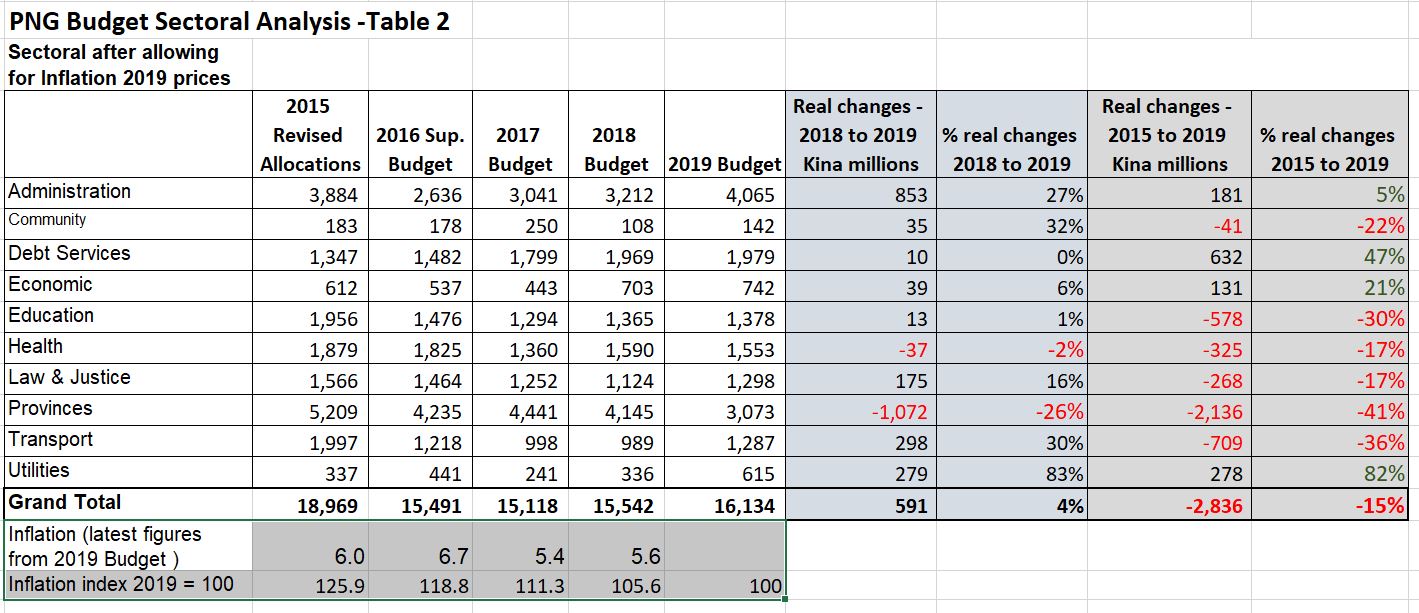

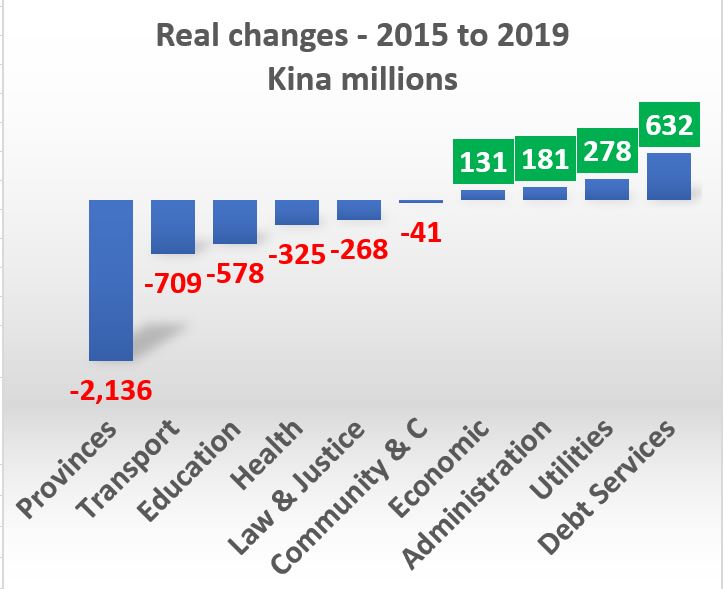

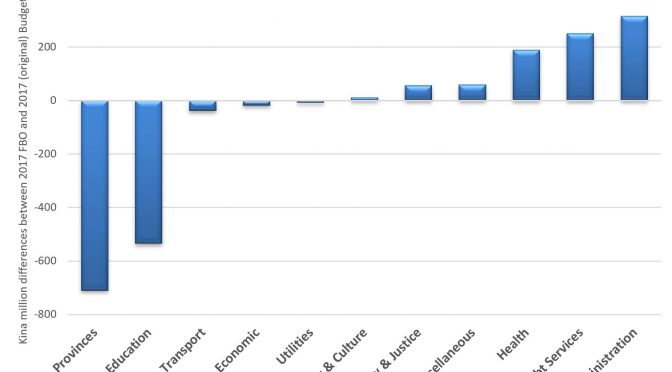

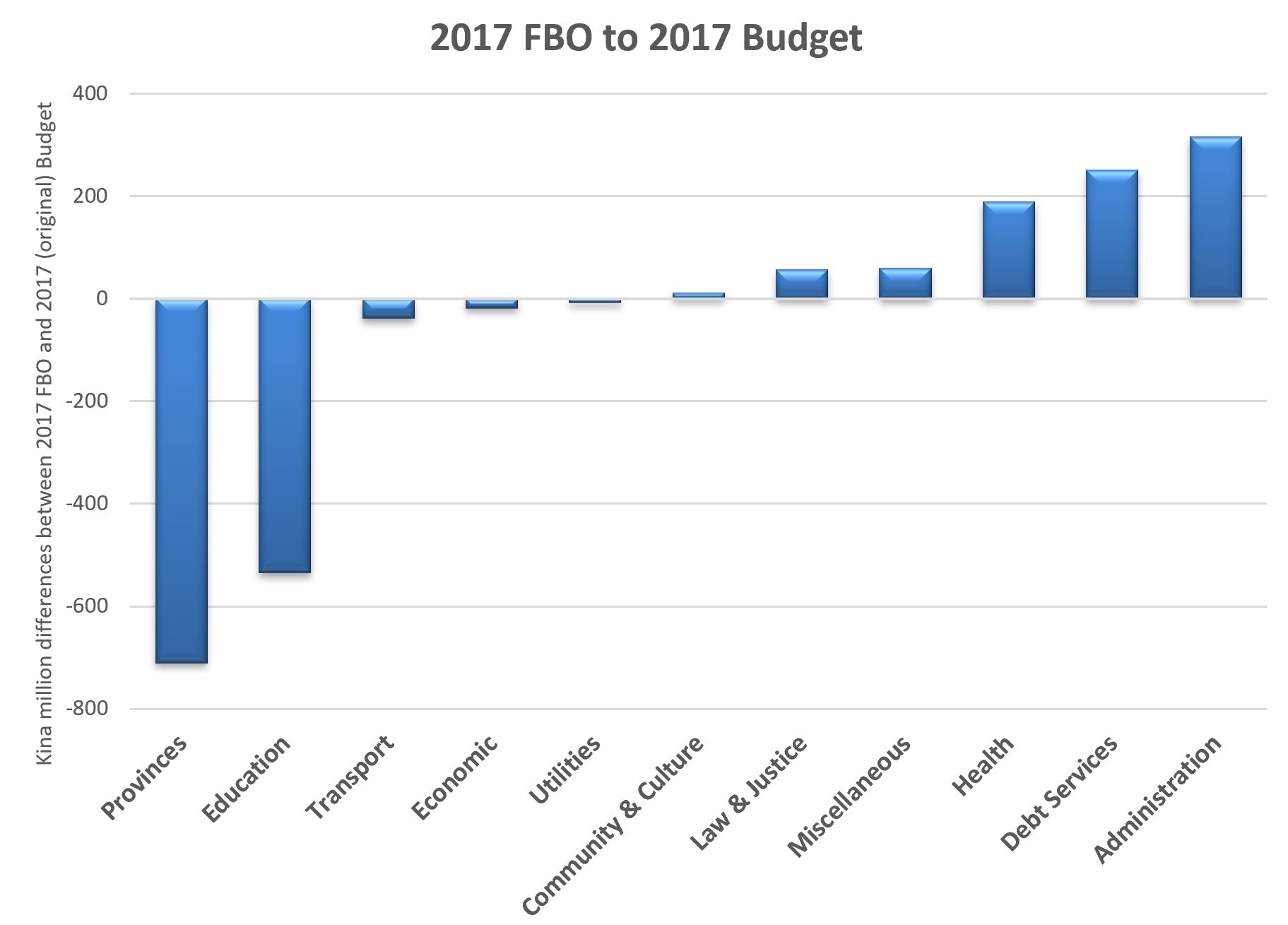

4, Gauge the government’s spending priorities

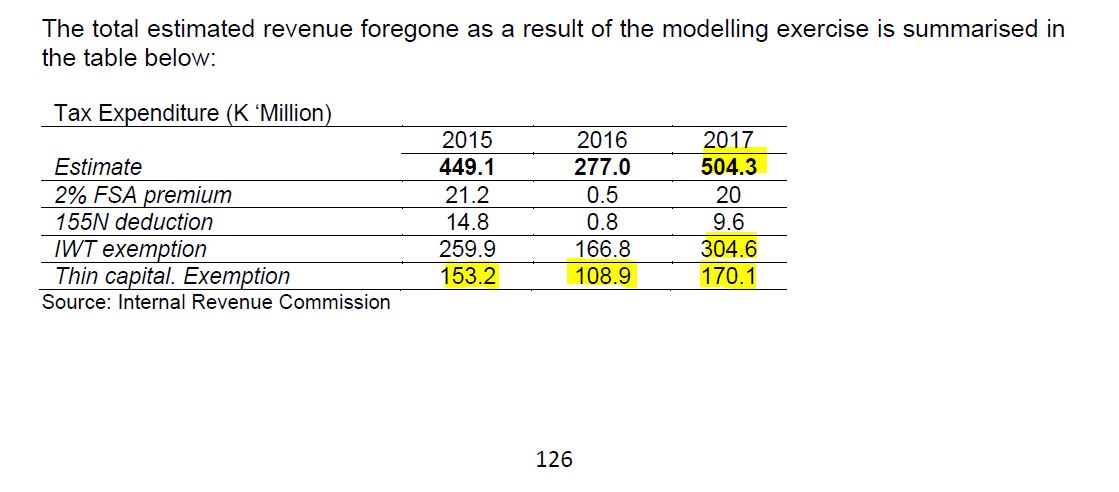

Part of this comes from looking at growth in expenditure on Compensation of Employees and Interest costs mentioned in step 3. There should also be a table that shows the break-up of expenditures between different sectors. Hopefully this is provided back in the Expenditure chapter – previously Chapter 6. The 2018 Budget didn’t have a good table comparing this expenditure through time – it only provided 2018 estimates. However, for the keen, here is a table that can be completed. This provides sectoral expenditure before inflation is taken into account (so nominal values) and one where inflation is included (real values). Taking inflation into account is important as the Kina can buy less in 2019 than it could back in 2015.

| PNG Budget Sectoral Analysis |

|

|

|

|

| Sectoral in Nominal Values |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2015 Revised Allocations |

2016 Sup.

Budget |

2017 Budget |

2018 Budget |

2019 Budget |

| Administration |

3,086 |

2,219 |

2,732 |

3,042 |

|

| Community & Culture |

146 |

150 |

225 |

102 |

|

| Debt Services |

1,070 |

1,248 |

1,616 |

1,865 |

|

| Economic |

486 |

452 |

398 |

666 |

|

| Education |

1,554 |

1,243 |

1,163 |

1,293 |

|

| Health |

1,492 |

1,537 |

1,222 |

1,506 |

|

| Law & Justice |

1,244 |

1,233 |

1,125 |

1,064 |

|

| Provinces |

4,138 |

3,566 |

3,990 |

3,925 |

|

| Transport |

1,586 |

1,025 |

897 |

937 |

|

| Utilities |

268 |

372 |

216 |

318 |

|

| Grand Total |

15,069 |

13,044 |

13,583 |

14,718 |

|

| Source: Dept. of Treasury. Budget documents 2015, 2016, 2017 (Table 12 ) and 2018 budget text except for interest costs based on actuals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Inflation (latest figures from BSP) |

6.0 |

6.7 |

5.4 |

5.9 |

|

| Inflation index 2019 = 100 |

126.2 |

119.1 |

111.6 |

105.9 |

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sectoral after allowing for Inflation 2019 prices |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2015 Revised Allocations |

2016 Sup.

Budget |

2017 Budget |

2018 Budget |

2019 Budget |

| Administration |

3,895 |

2,643 |

3,050 |

3,221 |

– |

| Community & Culture |

184 |

178 |

251 |

108 |

– |

| Debt Services |

1,351 |

1,486 |

1,804 |

1,975 |

– |

| Economic |

613 |

539 |

444 |

705 |

– |

| Education |

1,962 |

1,480 |

1,298 |

1,369 |

– |

| Health |

1,884 |

1,830 |

1,363 |

1,595 |

– |

| Law & Justice |

1,571 |

1,468 |

1,255 |

1,127 |

– |

| Provinces |

5,224 |

4,247 |

4,453 |

4,157 |

– |

| Transport |

2,003 |

1,221 |

1,001 |

992 |

– |

| Utilities |

338 |

442 |

241 |

337 |

– |

| Grand Total |

19,023 |

15,535 |

15,161 |

15,586 |

– |

5. Actually start reading some words!

The Foreword at the start of Volume 1 of the budget tends to include the key announcements and the budget “narrative” in only three or four pages – so much shorter than the typical waffle of the budget speech. It starts to become very interesting to compare the words in the foreword with the analysis of the tables covered in steps 1 to 4.

- Announcements.

Most of the big capital works programs should have been included in the 2018-2022 Medium Term Development Plan. So often the main announcements are actually around tax changes – and this often features in the write-up of the budget by the large accounting firms.

- Check on consistency between 2019 Budget and MTDP III

For the keen, you can attempt to compare the plans contained in MTDP III with some of the detail in the tables. The capital works programs contained in Volume 2 of MTDP III should match with the programs in Volume 3 of the 2019 Budget. A key issue is the link between the operational costs of the MTDP III and the 2019 Budget. This involves some hard work going through Volume 2 of the 2019 Budget which is huge – so large it has traditionally been printed in four separate volumes.

- Optimize food location

Stand close to the left hand side back door of the parliamentary lock-up when the nibblies come out – or at least that was the case several years ago. But possibly they have gone as a sign of budget austerity?

- Manage the volumes

The stack of budget volumes then somehow have to make it onto over-crowded library shelves. And on that note, if anyone has some old budget volumes (especially prior to 1990) which they not longer want to keep, please let me know! The only thing I like better than numbers is the history of numbers.

- Good luck and good night

Good luck! And I hope some of those hard-working PNG Treasury and National Planning Officers will be able to get some sleep with the 2019 Budget finally out of the way. Now just to get ready for the close of accounts, and then the process of monitoring. However, many in the private sector now have a long day ahead going through the numbers and reporting their analysis to their customers.