Summary

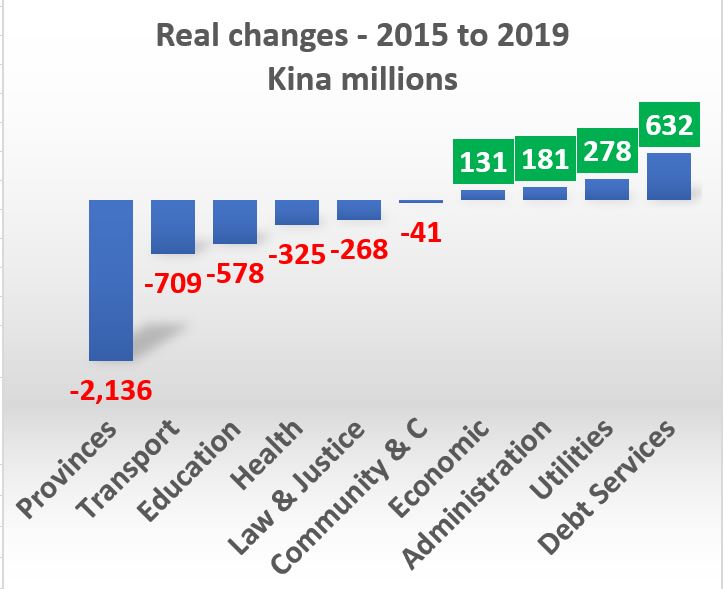

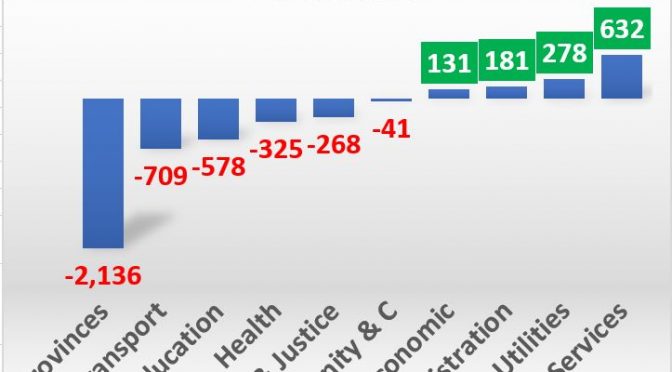

The 2019 PNG Budget is an expansionary one. The biggest sectoral feature of the budget is a transfer of K1,080 million in expenditure responsibilities from the Provinces sector to the Administrative Sector. The political ramifications of this will be interesting as it implies a transfer of power to the central government, away from Provinces and Districts, and allows more administrative control over parliament by the Executive. The big funding winners were the transport and utilities sectors. Despite medical shortages, the health sector was cut by 2 per cent after allowing for inflation. Education received only a 1% increase despite the Medium Term Planning requirements for a massive increase in teachers. Taking a longer-term perspective (from 2015 to 2019), there have been real cuts in transport of 36%, education of 30%, in health of 17%, in law and justice of 17%. The big longer-term winners have been utilities, debt service, the economic sector and administration.

Details

Methodology

Language in budgets always talk about supporting the so-called development “enablers” of health, education, infrastructure and law and order (the economic sector currently makes this list but it didn’t in some earlier plans). However, actual expenditure patterns have often not matched the policy language.

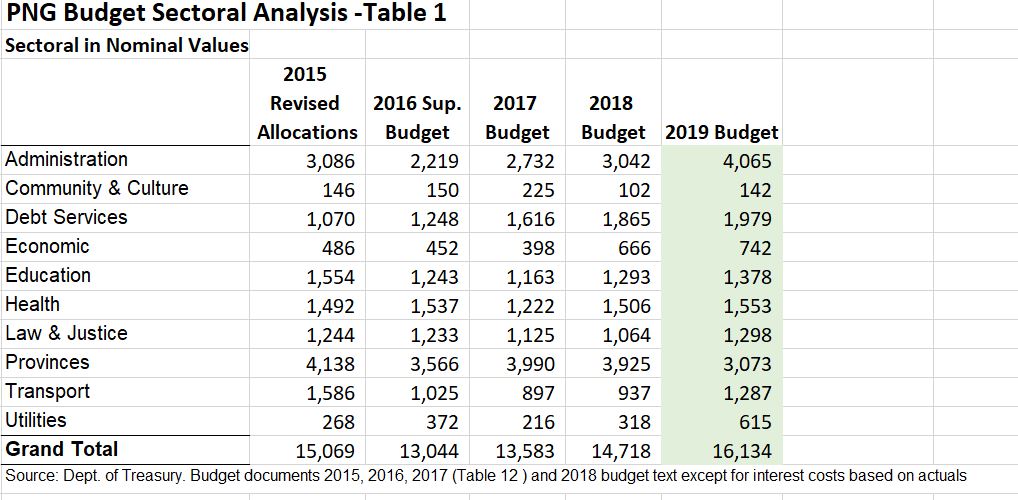

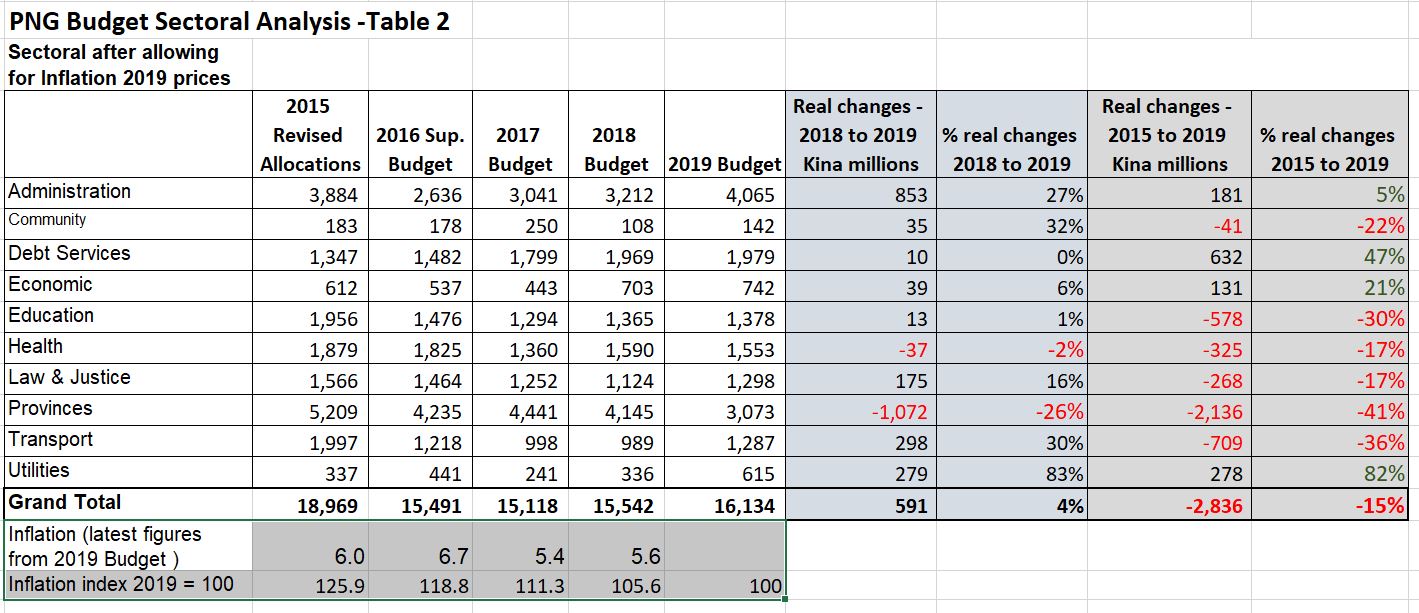

Below are tables providing sectoral expenditure figures from Budget documents covering 2015 to 2019. Adjustments have been made to debt service expenditure figures to match those in other tables in budget documents. As a word of warning, there is some judgement in determining if a particular item fits in one sector or another – the following tables draw on PNG Treasury’s assessments (presumably working with the Department of National Planning and Implementation). However, their information systems are imperfect.

The first table includes all figures in nominal values (so not allowing for inflation) – they come straight out of official budget figures. However, when doing comparisons over time, it is important to allow for the fact that a Kina in 2015 could buy more than it could today. Wages have gone up. Many goods and services cost more, although some could cost less due to technology improvements. Ideally, each sector should have its own price index but these are not available. Readers can use their own understanding of a price index for each sector if they wish. The approach used in the table below is to rely on the best available price index – PNG’s average inflation rate from its Consumer Price Index prepared by the National Statistics Office. The second table includes price changes by putting converting budget expenditures into 2019 values using the CPI. Specifically, allocations back in 2015 are now considered to be worth 26% more – a Kina in 2015 could, on average, buy 26% more things that it can now. 2016 items are on average worth 19% more, 2017 11% more and 2018 5.6% more. Readers can use their own price indexes if they wish.

As price changes through time are included, the second table is the better one for comparison through time. The table includes changes between the 2018 and 2019 budgets in the seventh and eighth columns, and between the 2015 and 2019 budgets in the ninth and tenth columns.

Provinces to Administrative

For the 2019 budget, by far the biggest change is the cut in the Provinces allocation by K1,072 million, or some 26%. This reflects shifting responsibilities for the District Services Improvement Program (DSIP) and the Provincial Services Improvement Program (PSIP) – worth a total of K1,080 million – to the Administrative sector. In the 2019 Budget documents, it is explained that the funding has been transferred to the Department of Implementation and Rural Development (DIRD). From a budgetary perspective, this is just a transfer of funds. From a political perspective, there are more significant implications. In Australia, such as transfer would cause a massive rift in Commonwealth and State relations. The large increase in local member and Governor constituency funding was a signature policy of the new O’Neill government in 2011 – a promise to provide K10 million to local members and Provincial Governors reflecting O’Neill’s earlier views on increased decentralisation. There have been serious doubts about whether K10 million was too much, whether it has been well spent, and whether there has been enough accountability for this expenditure. Possibly the major transfer could be seen as a good administrative move for fiscal accountability given poor reporting under previous systems, but it is likely to be a politically sensitive change. It is known that these constituency funds are highly political and are withheld or delayed from opposition members and used to increase the numbers on the government’s side of parliament. This practice is probably illegal under the constitution, and the opposition has threatened to take the government to court. By moving these funds under the control of a Minister, there is probably a way around this legal challenge by saying the relevant Minister has made an administrative decision not to release funds, for example because not enough detail had been provided in the quarterly report. If this was done in a consistent and transparent way, this could be an improvement. However, there clearly is scope for inconsistent treatment for political objectives. Given the importance and power of constituency funds, this appears to be a major shift in power from the Legislative to the Executive. Possibly expect fireworks behind what otherwise appears as a simple funds transfer.

Health

The 2019 Budget has a 2% real cut in health funding despite reports of major basic medicine shortages. It is hard to reconcile this real cut with the proposed massive increases in the number of health workers. Of course, the 17% real cut in funding over the last five years is also of concern and may have contributed to the outbreak of polio and increasing incidence of TB and Malaria. Talk of “free health” has always been a fiction with an allocation of only K20 million a year since 2012. Recent reports indicate parliamentarians have suffered from this deception when seeking even basic anti-malarial drugs.

Education

Education did slightly better with a 1% increase in real funding. Education was initially a big winner in 2011 with the introduction of Tuition-Fee Free Education at a cost of K600 million. This K600 million actually didn’t increase funding for the education system in terms of better schools and more teachers. Rather, it was primarily a cash transfer to parents as they no longer had to pay school fees. Education funding has been cut in real terms by 30% since 2015. There are reports that education standards have been declining – indeed, this has been acknowledged in the latest Medium-Term Development Plan.

At this stage, I have not gone through the detail of the significant funding for infrastructure and utilities. On the face of it, this would be welcome. Possibly, most of this funding could be from donor sources given recent announcements and the proposed shift in external funding towards infrastructure. The economic sector has held onto its large increase in 2018. The direct support for commercial equity in private operations has not worked in the past. Much more could be said – but to get this blog out quickly, just the numbers are provided in the following two tables:

One thought on “PNG 2019 Budget – Health cut despite polio and drug shortages, Administration big winner but political”

Comments are closed.