PNG and Mongolia have much in common economically. Indeed, the latest World Bank Global Economic Prospects report portrays them as near economic twins despite their historic, cultural and geo-political differences. If anything, Mongolia was considered the healthier of the two countries.

There is now one important economic difference – Mongolia last week recognised that it needed help from the international community. By doing so, it mobilised $US440 million in IMF funding and an estimated additional $US5.5 billion in additional cheap loan and grant assistance (much cheaper than Credit Suisse).

In contrast, the O’Neill government has failed to concede its economic mismanagement requires a similar solution – low cost financing conditional on improved economic policies. Foreign currency restrictions are the new norm for business, but this is hurting growth and discouraging further foreign investment.

There is much good that a similar assistance package could do for PNG’s citizens. The government’s arrogance should not stand in the way of the interests of its people.

Reporting twins

The World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects Report released in January 2017 was extraordinary in how closely it aligned policy issues in PNG and Mongolia. Indeed, when the World Bank talked of countries facing a particular issue, it was as if PNG and Mongolia were almost twins. PNG was mentioned eleven times in the text of the World Bank report (so excluding tables and boxes). On eight of these occasions, PNG was mentioned in the same sentence as Mongolia. Both countries were seen as having similar policy issues and suggestions (specific quotes and page references are at the end of this article).

There were only three occasions where PNG was mentioned without Mongolia – a factual reference to the PNG LNG project, PNG’s poor performance on the cost of Doing Business, and PNG having a particularly low rank on the Corruption Perception Index. On balance, one would rather not be in the company of PNG on the latter two measures.

Mongolia is also mentioned on three occasions without PNG. Two of these are put in the context of responding to the fall in commodity prices (policy tightening and contractionary monetary policy) as well as issues with the banking system.

Growth and poverty rates

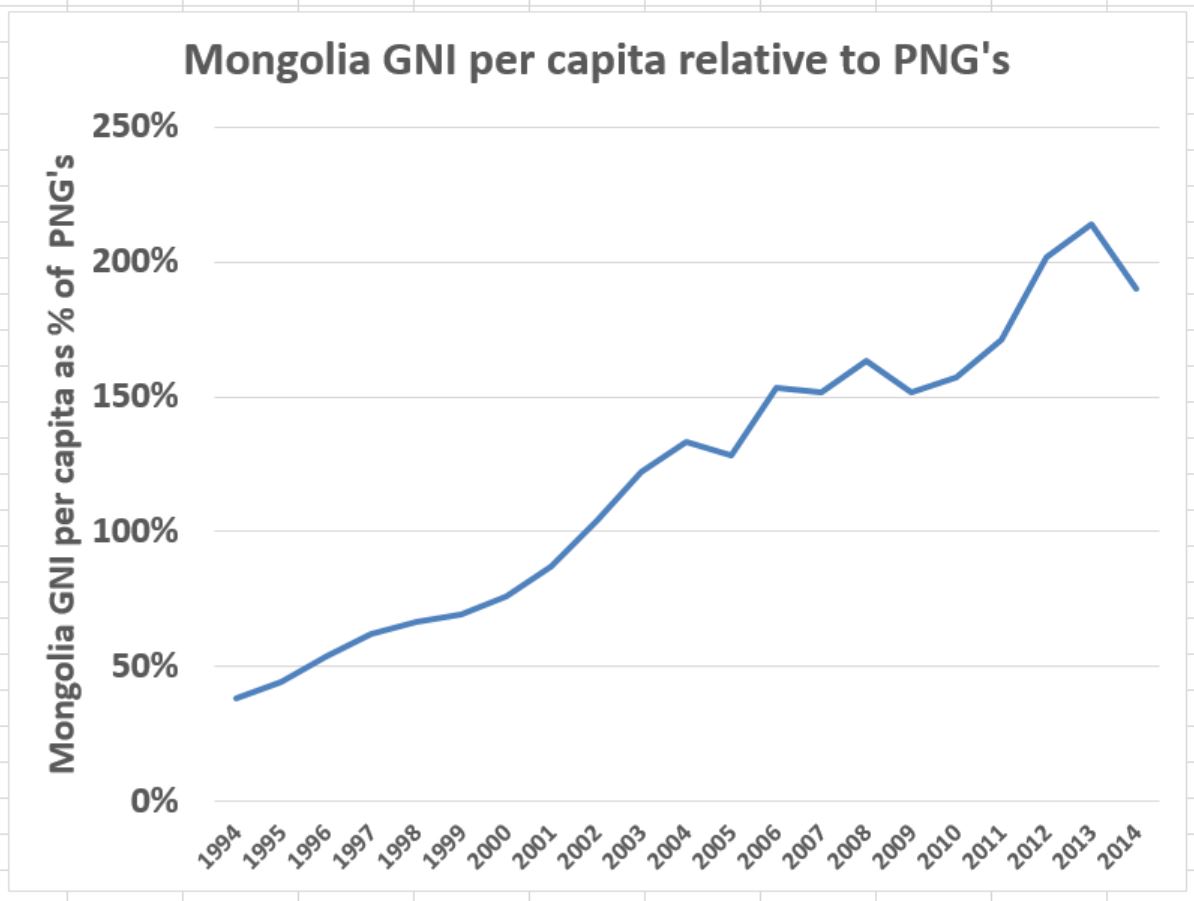

PNG and Mongolia are both recognised as large resource commodity exporters. Mongolia’s growth rates have been much higher than PNG’s in recent years – they recorded GDP growth rates of 17.5% in 2011, 12.4% in 2012 and 12.5% in 2013 before falling back to 8% in 2014. Building on much stronger growth rates over the previous decades, Mongolia’s average standard of living (measured in GNI per capita from World Bank data) is now nearly double PNG’s (190% in 2014) when thirty years ago is was less than half (38% in 1994). This shows the legacy of poor economic governance in the late 1990s (Mongolia had caught up to PNG’s level by 2002). To achieve PNG’s Vision 2050, PNG’s underlying growth rate must be lifted and this will must involve better policies with a people focus rather than a resource focus (see here).

Poverty rates in Mongolia have fallen dramatically from an estimated 39% in 2010 to 22% by 2014 (PNG’s latest figure is 40% from 2009).

Weak external positions

Just before the IMF program, Mongolia’s foreign reserves had fallen to 4 months of import cover. It has successfully borrowed on international markets but some big debt repayments were having to be repaid. (PNG can’t except through undisclosed deals with Credit Suisse). PNG’s import cover has fallen to 3.2 months according to IMF figures based on international standards (see here).

BPNG still claims PNG’s import coverage is over 10 months. Unfortunately, that type of delusional statistic hinders understanding of the need for policy reform. This is similar to the very slow pace of response by the O’Neill government to the fall in commodity prices in late 2014 – for six months they fiddled while claiming LNG prices were fixed and there would be no revenue impacts. Those that dared say otherwise were attacked.

Credit ratings

Both countries had similar credit ratings in 2014 of B1 (Moodys) – although Mongolia started to slide down through the ratings from mid-2014 while PNG did not start getting downgraded until early 2016. Despite this, Mongolia was successful in issuing a sovereign bond of $US500m just last year – something that international investors weren’t willing to provide to PNG with PNG’s failed sovereign bond.

Similarities but differences

There are of course differences between the two economies. Mongolia shares a land border with China so China’s slow-down in growth had a larger impact. In addition, Mongolia was even slower than PNG to respond to the fiscal impact of falling revenues and government debt grew even faster. Its banking system is also not as well regulated, and its development bank wasted more resources. However, it did continue with a flexible exchange rate and still has higher foreign exchange reserve coverage than PNG, it has a better environment for businesses to thrive, it has less corruption.

Even with these advantages, it recognised that some external assistance was needed given some poor policy economic decisions. Mongolia’s poor policy decisions were largely around budget policy. PNG’s poor decisions relate mainly to foreign exchange and monetary policy, corruption, excessive cuts in education, health and infrastructure spending, and poor inclusive economic growth policies.

There is much good that a similar assistance package could do for PNG’s citizens. The government’s arrogance should not stand in the way of the interests of its people.

Attachment

World Bank Global Economic Prospect January 2017

Text references to PNG and Mongolia

1. PNG and Mongolia Together

- In contrast, growth decelerated sharply in 2016 in a number of exporters in …. and East Asia and Pacific (Mongolia, Papua New Guinea).p18

- An acceleration of output in commodity importers was offset by softening activity in commodity exporters (Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Mongolia, Papua New Guinea), which continue to adjust to lower commodity prices.p84

- Growth slowdown was sharper in smaller, less diversified commodity exporters (Mongolia and Papua New Guinea), where the adjustment involved a correction of large imbalances.p84

- Sizable external financing requirements remain a source of vulnerability in Indonesia, while shallow policy buffers are a concern in smaller countries (Mongolia, Papua New Guinea, especially, …).p85

- The growth outlook has deteriorated markedly in several small commodity exporters of the region, where the terms-of-trade shock has exacerbated domestic vulnerabilities (Mongolia, Papua New Guinea).p86

- For commodity producers (Indonesia, Malaysia, Mongolia, Papua New Guinea), the new era of lower commodity prices underscores the need to enhance fiscal frameworks and improve the operations of institutions that manage commodity price volatility, such as sovereign wealth funds.p89

- Medium-term fiscal consolidation is needed to rebuild the policy buffers in a majority of countries (Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Mongolia, Papua New Guinea, Vietnam).p89

- This can be achieved through …. reduced dependence on revenue from energy sectors (Malaysia, Mongolia, Papua New Guinea) …..p89

2. PNG without Mongolia

- Part of the slowdown in Papua New Guinea was related to Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) output reaching capacity in 2015-16. p86

- Complementary reform priorities include improvements in the business climate and reductions in the cost of Doing Business (Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, Timor-Leste, and the small Pacific Islands; ADB 2016).p91

- Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands rank particularly low on the 2015 Corruption Perception Index reported by Transparency International and other governance indicators.p91

3. Mongolia without PNG

- Balance of payment pressures, currency weakness, and high inflation prompted these countries to embark on or continue policy tightening in the second half of 2016 despite soft economic activity (Azerbaijan, Angola, Nigeria, Mozambique, Mongolia).p18

- In some commodity exporters (Angola, Azerbaijan, Mongolia, Nigeria, Mozambique), the monetary policy stance still remains notably contractionary.p41

- Banking sector reforms rank high for improving efficiency and the allocation of capital in Cambodia, Lao PDR, Mongolia, and Vietnam.p90