[This article is being updated to reflect new NSO GDP figures.]

PNG’s 41st anniversary of Independence is tomorrow, so following are some reflections of its economic history.

Key elements of PNG’s Economic history since Independence

Summary

- The PNG economy is 3.3 times larger in real terms than at the time of Independence.

- For every Papua New Guinean at the time of independence, there are now, on average, 2.6 people.

- Jobs growth has not kept up with population growth.

- Real incomes have fallen by 4% since Independence – a long way from PNG’s understandable aspirations.

- PNG’s greatest policy mistake since Independence has been too much focus on natural resources (such as LNG, or gold, or logging) rather than people resources.

- Focusing on natural resources has tended to create a dualistic economy with development benefits captured by few.

- The resource sector has had very limited impacts on the vast majority of people in PNG and it is highly variable. The start of production from the Kutubu oil fields and new mines in the early 1990s led to massive increases in measured GDP of 36% between 1991 and 1994 – even larger than the 25% real GDP increase over 2014 and 2015 driven by the commencement of the PNG LNG project. However, by 1994, PNG had fallen into recession and cash and foreign exchange shortages. And by 2015, history is repeating itself as PNG has fallen into recession again after the promise of rivers of resource revenues led to poor fiscal, monetary and structural policies.

- The resource curse also leads to a “strong Kina”.

- A “strong Kina” hurts local exporters (including rural farmers), local production and encourages people to invest outside of PNG rather than in PNG. It is likely a key reason why PNG has missed trade globalization. A more competitive price setting with the rest of the world is the easiest policy change to help steer PNG on a better development course.

- There is widespread and growing concern in PNG about a decline in the quality of government service delivery. In addition to concerns about quality and governance, one element of this is that the real level of government expenditure per person has decreased since independence from K1,873 to K1,851.

- With larger budget deficits and greater local tax collections, the primary cause for this decline in government expenditure is the significant decline in aid per head. This has dropped dramatically – from around K660 per person down to K170 – a real drop in support per capita of 75 per cent. Falling service delivery is strongly linked to the fall in Australian aid.

- PNG has enormous potential and opportunities. This potential has not been delivered to its people.

- May PNG have better policies, better institutions and a more inclusive form of development over the next four decades to better meet the deserved aspirations of its people.

Economic growth since Independence

The PNG economy, after allowing for inflation, is 3.3 times larger than in 1975. Many people doubted that this would be possible at the time of Independence given the challenges and uncertainties facing the new country. This growth is probably clearest in a place such as Port Moresby – it is a much more modern city with freeways, flyovers, luxury hotels, traffic jams, pollution, large shopping complexes and many taller buildings downtown. This in part reflects the strong urban bias of PNG’s economic policies.

For PNG, almost all of this real growth can be accounted for from population increases. Since Independence, the population has increased from 2.9 million to an estimated 7.6 million. For every Papua New Guinean at the time of independence, there are now, on average, 2.6 people.

The total number of people in the formal sector has slightly more than doubled according to Bank of PNG business surveys. While jobs growth is positive (a 2.1 times increase from 1978 to 2014), it is disappointing that it has not even kept up with population (a 2.6 times increase). In other words, the share of working-age people getting jobs in the formal economy has been falling. This is not inclusive growth.

PNG is described as a resource dependent economy. This is unusual terminology as the non-resource sector has accounted for between a high of 93% of the economy (in 1984) and its lowest share of still 70% (in 2006). The resource sector has had very limited impacts on the vast majority of people in PNG and it is highly variable. The start of production from the Kutubu oil fields and new mines in the early 1990s led to massive increases in measured GDP of around 36% between 1991 and 1994 – even larger than the 25% real GDP increase over 2014 and 2015 driven by the commencement of the PNG LNG project. However, by 1994, PNG had fallen into recession. And by 2015, history is repeating itself as PNG has probably fallen into recession again after the promise of rivers of resource revenues led to poor fiscal, monetary and structural policies.

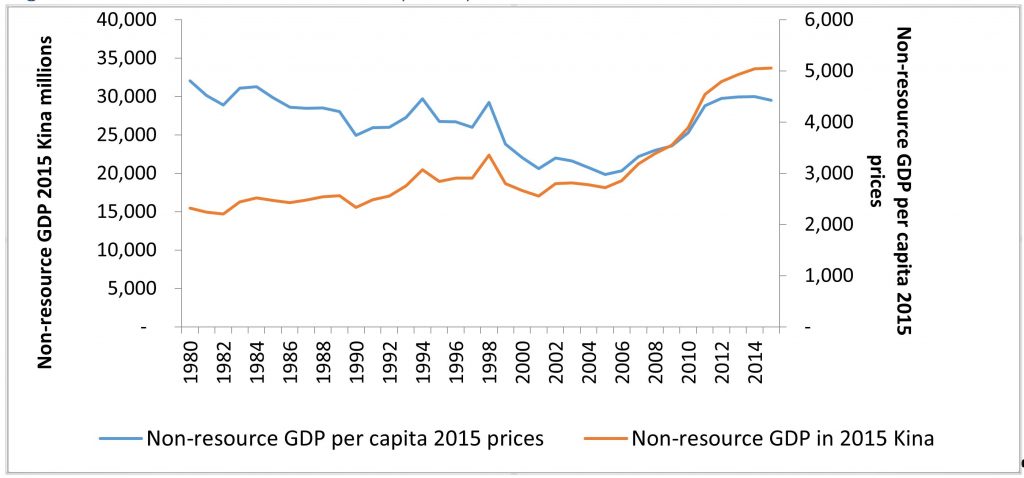

A better measure of economic performance is to focus on non-resource GDP – shown in orange in Figure 1 (reliable non-resource GDP information is only available from 1980). Non-resource GDP grew very slowly for the first two decades from 1980. Over the late 2000s, there was more rapid growth, but this had slowed by 2010.

Figure 1: Non-resource GDP and GDP per capita in 2015 Kina

An even better measure of economic performance is using per capita figures – so how much income is generally available per person. This is shown in the blue line. Unfortunately, this line trended down through both the 1980s and 1990s. The sharpest decline was related to the economic crisis of the late 1990s. A pattern of recovery slowly commenced from 2005, but this has flattened out since 2012 and is now in serious decline. By 2015, using a five-year average, incomes are four per cent lower than they were in 1980 (the 5-year average of real non-resource GDP per capita was K4,604 from 1980 to 1984 and K4,443 from 2011 to 2015 – a drop of 4 per cent – the drop in real incomes is larger if the comparison is just between 1980 and 2015 – a drop of 8 per cent.) On this key measure of economic well-being, real incomes in PNG have gone backwards. And emerging data for 2016 indicates this continues to get worse.

This is very disappointing, and a long way from the aspirations of people at the time of Independence. It is also a long way from future aspirations shown in Vision 2050. Why is this so?

PNG’s Resource curse – history repeating itself

PNG’s greatest curse flows from the intersection of nature’s resource gifts and economics. The “resource curse” has and continues to destroy many economies. A cure was tried in PNG (through the Mineral Resource Stabilisation Fund – and this was a better model than the current flawed Sovereign Wealth Fund model), but the combination of corruption, poor politics and poor economic policy means the resource curse remains the greatest burden hindering real development. The resource curse underpinned the Bougainville civil war and still risks fracturing the PNG state with daily newspaper reports of landowners being unhappy with their share of resource benefits. In a slow and insidious way, the resource curse impacts on the exchange rate, paralysing opportunities for integrating PNG into the Asian century.

PNG’s greatest policy mistake since Independence has been too much focus on natural resources (such as LNG, or gold, or logging) rather than people resources. Focusing development efforts around people, such as support for smallholder agriculture or encouraging the informal sector, tends to lead to a pattern of development with more widespread and inclusive benefits. Focusing on natural resources has tended to create a dualistic economy with development benefits captured by few.

I am saddened when I read comments in PNG lamenting the decline of the Kina relative to the US dollar since a peak was reached in 2013. A “weak” Kina is considered a source of national shame. As an economist, this is a stupid argument – but more profoundly for PNG’s development, it is a dangerous argument.

For the over 2 million people who earn most of their income from cash cropping, a “strong” Kina is bad news as it means they get less Kina for every bag of coffee or cocoa that they sell. What is known as a “strong” Kina is in fact very bad for all exports and trade competing industries such as agriculture, fisheries, tourism and SMEs. However, for a public servant in Port Moresby, a “strong” Kina means that a bag of rice or a new digital TV will become less expensive.

A “strong” Kina also has social implications. It creates a strong incentive to leave the cash cropping opportunities in rural areas and move to an urban area in search of a formal sector wage. It has strong gender impacts as it undermines the value of the work of women in domestic agriculture. It increases the incentives for Papua New Guineans to send their money overseas either for property investments in Cairns or to send their children to school overseas. It hinders foreign investment in PNG by making it more expensive relative to other destinations.

This one price, the exchange rate, has very powerful impacts on nearly all aspects of development.

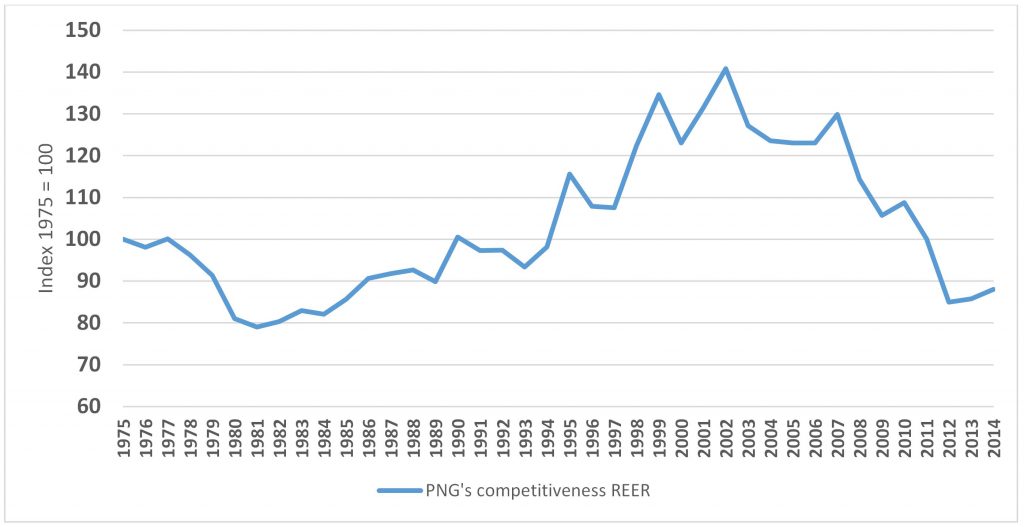

The resource curse leads to a “strong Kina”. The best exchange rate measure is something called the “real effective exchange rate” or REER. This measures movements in the Kina relative to its major trading partners as well as inflation rate differences. In the following graph, the higher the curve, the more competitive the PNG economy.

Figure 2: PNG’s competiveness (shown by the real effective exchange rate)

The initial “hard Kina” policy in the early years after independence was arguably justified on the basis of maintaining macroeconomic stability – but it certainly decreased PNG’s competitiveness at this crucial time in the country’s development. The floating of the Kina in 1994 in response to the poor policies around the Kutubu oil resource boom started an on-going improvement in competitiveness until 2007. However, the effects of the PNG LNG project and poor policy interference in the exchange rate have dropped competitiveness levels to less than at the time of Independence. Improving PNG’s level of competitiveness through the exchange rate is possibly the most important single policy instrument for improving PNG’s development prospects.

However, improving competitiveness will have major distributional implications – those reliant on exports will become better off, those reliant on imports will become worse off. This will generally benefit rural areas and hurt public servants and many urban area residents. It will benefit businesses reliant mainly on domestic PNG production and hurt businesses reliant mainly on imports. There are dynamic elements to such an adjustment. The short-term losers will tend to speak out loudly while the long-term gains for SMEs and new businesses suited to the more internationally competitive opportunities in the Asian century will be silent. Sustaining such a policy is politically difficult. And as there is no “silver bullet” in development, this change needs to be complemented by many general improvements in public policy (such as better regulation, more inclusive and sustainable policies, appropriate infrastructure, improved law and order, less corruption, control of wages and prices, greater gender equality and a better educated and healthier workforce).

Government expenditure falls driven by falls in Australian aid

There is widespread and growing concern in PNG about a decline in the quality of government service delivery, although the experience differs between provinces and even sectors (for example, education appears to be doing better than health).

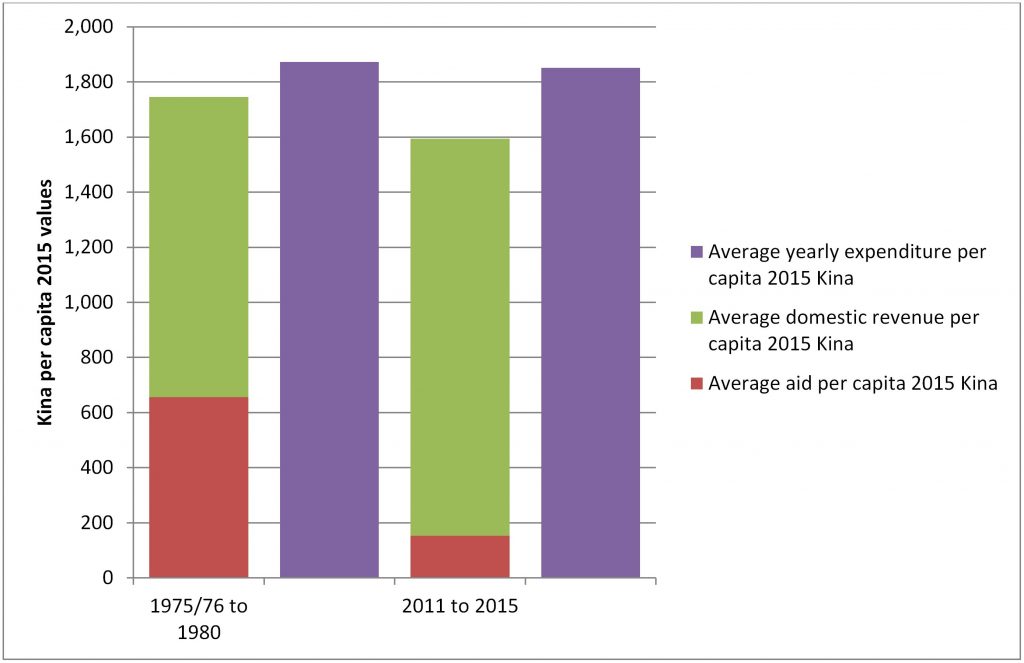

Amongst these many complaints, there are some mitigating factors. Even maintaining basic service delivery was going to be a challenge given the very large increases in population requiring massive increases in teachers and classrooms and medical staff. A rarely mentioned fact is that the real level of government expenditure per person has decreased since independence (see figure 3). Taking five year averages to smooth out annual fluctuations, real expenditure per person has dropped from K1,873 to K1,851 (the purple columns). So a slight decline in services could be expected even if there wasn’t an increase in corruption or a decrease in the ability of institutions to deliver.

What have been the drivers of this decline? Fiscal policy has been loosened with larger deficits – so this isn’t the cause. Domestic revenue raising per head (the green columns) has risen by just under 30 per cent – a credible performance given the fall in non-resource GDP per capita since independence. The primary cause is the significant decline in aid per head. This has dropped dramatically – from around K660 per person down to K170 – a real drop in support per capita of 75 per cent. Falling service delivery is strongly linked to the fall in Australian aid.

Figure 3: PNG’s budget structure

Conclusion

PNG has enormous potential and opportunities. This potential has not been delivered to its people. PNG is burdened with too much of its past. There are still too many remnants of it being a 1975 colony of Australia rather than a modernizing Indo-Pacific nation. Overall, I remain an optimist about PNG’s future but there are still decades ahead of often painful development choices and learnings.

There are many interacting elements that help improve well-being – and the most important ones are not economic ones. However, if I was to suggest one key change in policy priority it would be to focus on people rather than resources.

The resource focus and subsequent “strong” Kina aspirations are yokes on development. This manifests itself through the myth of a “strong” Kina. This myth is biased against local exporters, local production and encourages people to invest outside of PNG rather than in PNG. It is likely a key reason why PNG has missed trade globalization. A more competitive price setting with the rest of the world is the easiest policy change to help steer PNG on a better development course. And it will help deal with nationalistic tendencies without imposing more destructive policies such as import bans or inefficient government led monopolies.

May PNG have better policies, better institutions and a more inclusive form of development over the next four decades to better meet the deserved aspirations of its people.