The Electoral Commissioner on Friday 21 issued a press release responding to claims about the 2017 voter roll.

He misrepresents seriously what my earlier analysis showed. What is more intriguing is that he seriously misrepresents what he himself has tried to show – he has scored some home goals.

First, on the ludicrous claim that one cannot compare the 2017 electoral roll with the 2011 census (claiming that they are apples and oranges), he made this same comparison on 9 April – “This (new electoral enrolment forms) may reach one million and over and may contribute to a highly inflated 2017 roll as the number of eligible voters on the roll may equal or exceed the PNG population figure which is 7.5 million as per the 2011 census figures.” see here and here. So why can he make the comparison but not others?

Second, doing a check on the ratio of the electoral roll to the expected voting age population is a very standard and fundamental check on roll integrity. This comparison is used in assessing electoral fairness throughout the world – including in PNG. For example, in the DFAT assessment of its assistance to the PNG Electoral Commission from 2002 to 2012 – see here – it constantly uses the ratio of the roll to the population as the basis for assessing the quality of the electoral roll and Australia’s previous assistance in this area (see paras 3.9, 4.14, 4.16, 4.19, 4.29, 4.32, 4.34).

Third, he then indicates that I was trying to do a comparison between the quality of the 2012 electoral roll and the 2017 roll. I would have liked to have done this comparison, but the Electoral Commission had not previously released the data which allowed a test of a bias towards PNC electorates. So all I had previously been able to do was an examination of the 2017 roll. And all indications are that it is incredibly biased towards the PNC – see here and here. The Electoral Commissioner should unquestionable release more information to the public – doing so would have helped stop the devastating blow to PNG’s election credibility when the Electoral Advisory Committee felt it had to resign as it wasn’t provided with such information.

Fourth, an unintended outcome of providing additional information is that a very broad comparison can now be made between electoral bias in the 2012 and 2017 electoral rolls. Gamato has shot himself in the foot.

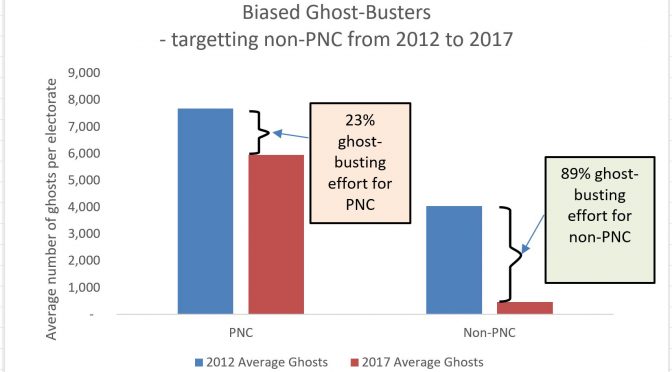

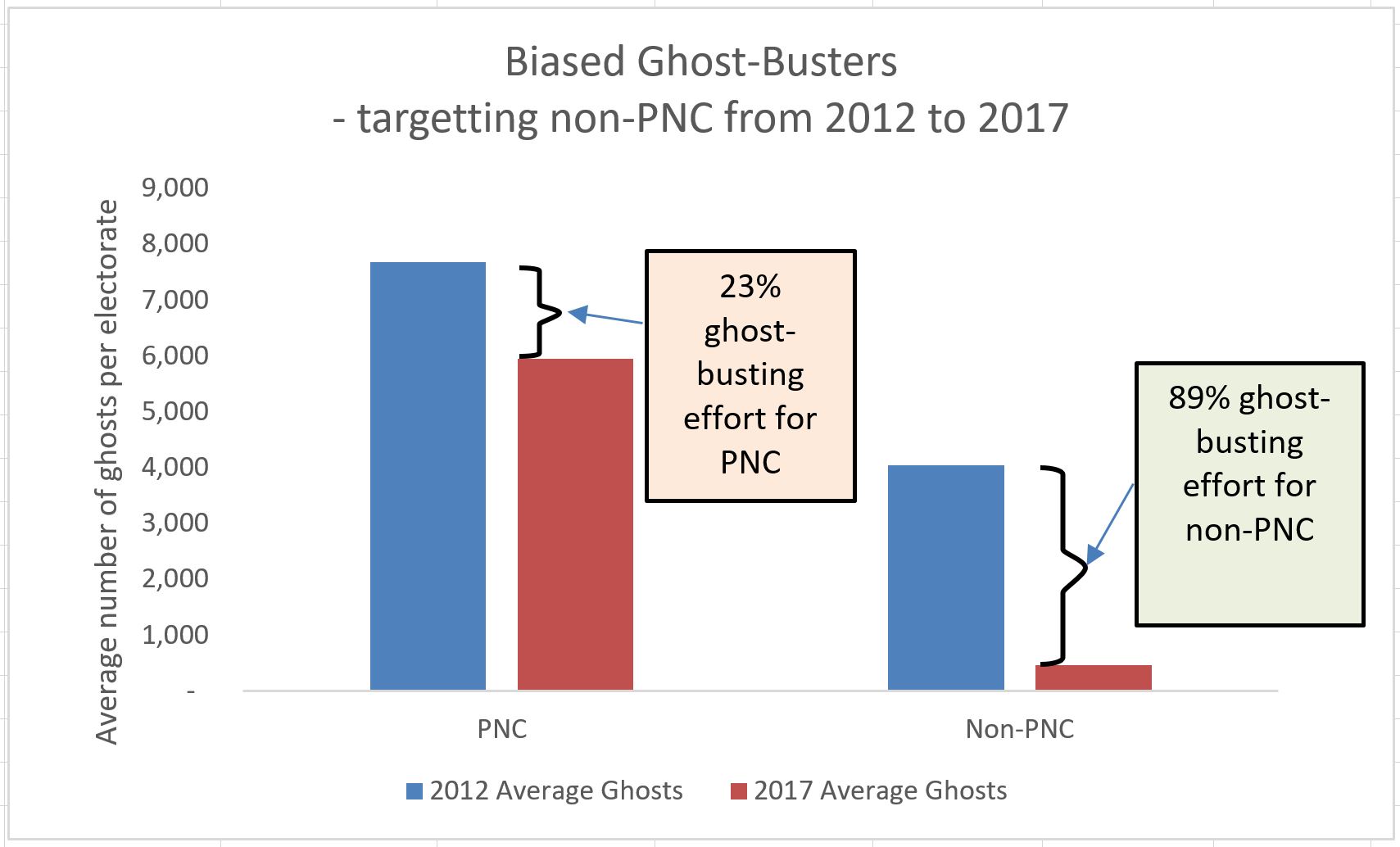

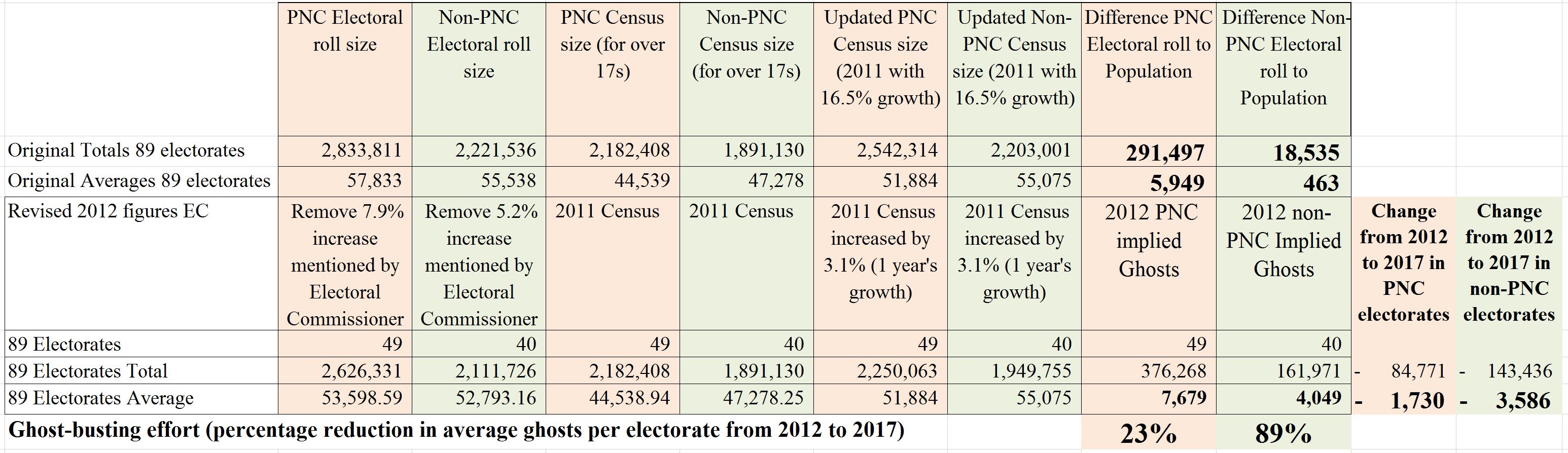

Although there is a commendable reduction in the total number of “excess” electors, or inflated rolls, or “ghost voters” on the roll, the reduction has been concentrated in non-PNC areas. So while it is commendable that the average size of ghost voters has fallen from 7,500 per PNC electorate to 6,000 per electorate, it is extraordinary that the reduction in non-PNC areas has been so much greater (from around 4,000 per electorate to under 500 – and a negative number when statistical outliers excluded).

This ghost-busting effort is 23% for PNC areas – a pretty poor effort. However, it is 89% for non-PNC areas – in some ways a noteworthy achievement. Details provided in tables below, and summarised in the following graph. This is a very biased pattern of “ghost-busting” which helps O’Neill’s position.

If you were looking to get rid of a lot more “ghosts” in non-government electorates, it seems as if you know who you’d want to call.

Gamota should resign. It is difficult to know how this can be handled in the current situation where he has so much power to shape the election’s outcome.

Despite all the abuse of the powers of incumbency by O’Neill, he appears to have underestimated the strength of the people’s desire for change.

May there be a unified front from those seeking a change, one needed to deal with the corruption, poor governance and disappointing economic and budgetary and exchange rate performance of the last five years.

Extract from 21 July Press Release from PNG Electoral Commission

4. Response to claims by Blogger Paul Flanagan about 2017 Voter Roll

At my last briefing, questions were raised by an article by a blogger Paul Flanagan.

We have looked into this. Mr Flanagan made comparisons between the 2017 voter roll and the 2011 census.

His claim is that the number of people on the 2017 voter roll in seats held by the PNC increased by a higher percentage than non-PNC seats.

But he was comparing the 2017 roll and the 2011 census. His argument is based on a false comparison.

The Electoral Commission has nothing to do with the 2011 census. We do not compile the census.

Furthermore, Electoral Roll and Census use a different methodology and have different requirements.

Therefore the comparison is not valid. He is comparing apples to oranges.

There is no ‘army of ghost voters’ as Mr Flanagan claims.

The Electoral Commission is concerned with the electoral roll. The overall growth in the roll from 2012 to 2017 was 7%, or 318,000 people.

For someone to claim there are 300,000 ‘ghost voters’ for one political coalition is nonsensical. It simply cannot be substantiated.

Between the 2012 roll and the 2017 roll, the increase in numbers in PNC and non-PNC seats is in fact marginally lower in non-PNC seats – by 1.1%.

In PNC held seats there was growth of 5.9%, and in non-PNC seats growth of 7% in numbers on the roll.

If we use Mr Flanagan’s comparison of 49 PNC and PNC-endorsed seats to 40 non-PNC seats, the growth figures are 7.9% and 5.2% respectively.

But I would point out that most PNC-endorsed seats are in the Highlands.

There was bigger than average roll growth across the board, in seats won by all parties.

Let me be clear: the Election Commission is an independent Constitutional Office. We do not work for the PNC or any other political party. I resent that inference and reject it outright and completely.

As I have said previously, there have been concerns with the voter roll. It is not perfect, and we are looking into it. We will conduct a full review. But such problems are not unique to the 2017 election.

The sheer logistical feats of staging an election here must not be ignored. We are a country of about 7.6-8 million people, with more than 800 different languages, high rates of illiteracy, poor infrastructure, areas without road access.

In parts of the country like the Highlands, there is a robust culture that adds its own complications to holding elections.

Papua New Guinea faces multiple challenges in staging an election.

We are not perfect, but we are making progress.

The Election Commission is committed to improvement, while at times operating with resources which were below expectations.